The view from Larry Racioppo’s deck at his home in Belle Harbor, Queens following Hurricane Sandy (Credit: All photos by Larry Racioppo)

As Hurricane Sandy started making its way to the Rockaways, Larry Racioppo went down to his basement and put all his tools up on a five-foot table. He’d heard the warnings, but his wife Barbara and their black lab Juno did not want to leave their Belle Harbor, Queens home, so they hunkered down to wait out the storm even though their house sits less than 20 yards from the beach.

“I don’t know if we’re stubborn or dumb, but I didn’t realize how bad Sandy was until they shut down the bridge,” Racioppo, 65, says. “We took on seven-feet of water and lost power for four months, but at least the gas line didn’t break. We heated our house with the fireplace, cooked simple meals on our stove top or ate from food trucks, and listened to the radio at night. It was eerie, quiet and desolate, but we never left.”

Fortunately for Racioppo, there was one house with a fence that provided just enough of a buffer between his home and Sandy’s massive waves to prevent total devastation. He lost some $10,000 worth of tools and other possessions, but not the three things that matter most: Barbara, Juno and a lifetime of creative work. Racioppo had long been astute enough to keep his pictures, equipment, negatives, cameras and everything else that goes along with it upstairs.

All things considered, they came through it with bumps and bruises, but no knockout punch. So after the initial impact of Hurricane Sandy began to ebb, Racioppo did what he always does, albeit reluctantly. He didn’t want to capitalize on his neighbors’ misery, but a photographer has to document his surroundings, so he grabbed a camera and headed out into the waterlogged streets close to home.

Larry Racioppo is New York City through and through. Raised in Park Slope, he’s a product of the 1950s with its Roman Catholic schooling, Sunday Italian dinners, Catholic Youth Organization basketball and fathers who worked as firemen, longshoremen, cops, garbagemen, restaurateurs and the like. But he also came of age in the 1960s, dropping out of Fordham University in ‘68 and heading out west to work among the migrants in the Santa Clara Valley as a VISTA volunteer. It was in Gilroy, California, the “Garlic Capital of the World,” where he began messing around with a friend’s camera. He had no experience, let alone any formal training, but Racioppo had found what the old parish priests referred to as a calling.

“In 1970, I decided to head back to New York City, so I bought a car for $120, a Nikon Range Finder camera for $35, and zigzagged across the country, taking the long route from Idaho to Mexico, snapping pictures along the way,” he says. “I spent every dollar I had on that trip. By the time I got back to the Verrazano Bridge, I had $8 left to my name, but I knew I wanted to be a photographer.”

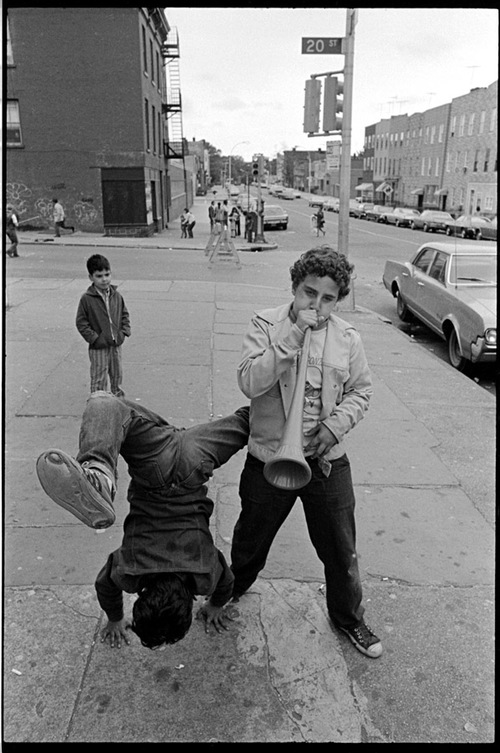

Racioppo kept on taking pictures, particularly of the everyday folk in his new Sunset Park community, where he rented a little storefront and set up a black-and-white darkroom. Along the way, he finished his degree in communications at Fordham, took a basic photography course at the School of Visual Arts and, in 1975, got a Master’s in TV and Radio Production from Brooklyn College, all the while earning his keep driving a cab and waiting tables at a fancy Upper East Side joint, far from the egg-on-a-roll longshoreman he was snapping in the off-hours. Eventually, Racioppo became an assistant to renowned photographer Phil Marco, which gave him a crash course in the refined professional world of taking pictures, particularly still life. But it never called to him like the streets. In 1980, Racioppo had his first book published, Halloween, featuring neighborhood kids trick-or-treating in their cheap ‘70s-era costumes.

And yet, even in those supposedly glorious days of the Gotham artiste, it wasn’t easy making a living. “I never gave up, but it got harder and harder to do the things I wanted to do, to take straightforward pictures of regular New Yorkers and their neighborhoods in the same way as my hero Walker Evans,” he says. “I needed a job, so I went into construction.”

Flash forward nearly 10 years, and Racioppo is restoring brownstones and photographing his world whenever he can. On one fortuitous job, he met a woman who wanted pictures of her restoration taken. They got to talking and Racioppo told her, “I’m actually better at photography than construction.” She was a press officer in city government, one thing led to another, and soon thereafter, he landed what turned out to be his dream gig.

In 1989, Mayor Ed Koch was embarking on a 10-year project to fix the city’s housing crisis, a massive effort that saw 150,000 units built in low-income areas and came to define his legacy. Koch was savvy enough to grasp that the only way to get New Yorkers on board was to show them the grim, ugly, filthy, rat-infested truth, which more or less became Racioppo’s marching orders. He’d gone to work as an in-house photographer for the Department of Housing Preservation & Development. “It was vocation meeting avocation, but I never would have stayed with it for more than few years if the pictures were going to be HPD propaganda,” he says. “The Housing Commissioners wanted to know what was really going on, so I had freedom to document the realities of public housing.”

Racioppo, armed only with a camera and a notepad, walked right into the South Bronx, Brownsville, Bed-Stuy, Clinton Hill, East New York, Fort Greene — all the places (back then, anyway) where white people who didn’t carry a badge rarely ventured. Racioppo’s a big guy, possessed with a native’s street sense, so once he explained what he was doing, people never gave him a hard time, in part because they were the ones stuck in decrepit, unlivable housing. “Guys would be hanging out on the steps, drinking beer and smoking weed, and when I’d take out my camera, they would all scatter — except inevitably, one guy would cross his arms and give a menacing pose, then laugh and jump away before I pressed the shutter,” he says. “I didn’t care, I wasn’t threatened. I was on to the next abandoned building or vacant lot.”

The only time Racioppo ever felt conflicted was when he was sent by HPD to accompany the police as they raided an East Village tenement filled with squatters. He thought he’d find a bunch of his artist friends, but they would’ve understood. As usual, he was mired in the New York City muck taking pictures.

Racioppo stayed on the job for 22 years, retiring from HPD in 2011. He did, however, take a year off after winning a Guggenheim fellowship in 1997. His winning submission was a group of huge 17 x 51 panoramic urban landscapes on 20 x 60 paper. The award paid $32,000, but unlike two fellow honorees he knew who went off to Russia and Vietnam, Racioppo returned to the same gritty neighborhoods with a notebook denoting all the places he hadn’t had enough time to photograph.

His day job fueled his creativity, which is evident in his work even now. There is no pretentiousness, overt attempts to be arty or forced cutting-edge posturing in any of Racioppo’s pictures. He’s a man who took what he learned from the Society of Jesus seriously and remains committed to social justice through the lens. When I ask him about life in Belle Harbor, he sings its praises, but also shakes his head ruefully, saying, “There’s a lot of firefighters and cops down here who complain that Obama’s a socialist. Can you believe that? Union guys.”

Racioppo’s humanist values come through in his work, whether in his collection of “Good Friday” shots or the portraits of guys in the “Scrap” trade. He also has a tremendous eye for the underpinnings of the city, be it the requisite “Before and After” shots, random old school “Interiors” or the long-since forgotten and abandoned theaters and churches in “All This Useless Beauty.”

Like many a kid raised on urban playgrounds, Racioppo is a basketball junkie, even if he had to give up the game a few years back because his body won’t do what it used to. Basketball is what first drew me to his work, as his series of random hoops throughout New York City was exhibited on a temporary wooden wall hiding a construction site under the Manhattan Bridge. It’s an amazing set of pictures, showing the resiliency and resourcefulness of ballers across the borough blacktops. The simple unadorned shots of iron hoops, wooden backboards and the by-necessity plastic milk crates say a lot about playing ball no matter what unexpected or undeserved circumstances New York City life throws at you.

You know, like the largest Atlantic tropical storm ever.

At the opening night party for Rising Waters, an exhibition of Hurricane Sandy photos at the Museum of the City of New York, Racioppo is greeting friends and well-wishers, but he stands apart from the platform — which he made out of Sandy wood scraps — where his featured work sits. He’s content to let “Larry’s Sandy Diary” speak for itself. It’s a large 22-page work with a plywood cover festooned in orange construction fencing and a waterlogged camera. It showcases pictures from the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy and the recovery efforts, along with Racioppo’s handwritten notes of what he bore witness to. He kept it close to home, never venturing to nearby burned-out Breezy Point because he felt that would have been exploitative. In many ways, “Larry’s Sandy Diary” is much more personal than his previous work because he wasn’t simply shooting what he saw, he was living it. In an exhibition of 200 photos culled from 10,000 submissions, it’s the intimacy of Racioppo’s work that stands out.

“It’s a Golden Age for photography in New York City and Rising Waters is proof. It’s a strong, powerful show featuring great professionals and on-the-spot-amateurs alike. I’m proud to be a part of it,” he says. “It’s funny, this morning, the water was so calm out on the ocean. The Atlantic was like a lake ….”

Tides come in, tides go out. New York City changes, Racioppo takes pictures.

The Rising Waters exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York runs through March 2, 2014.

Originally from Montana, Patrick Sauer lives in Brooklyn. When he’s not a stay-at-home-dad, he writes for ESPN, Narratively, The Classical, Biographile, SB Nation … anywhere that wants him, really. Follow him at @pjsauer or patrickjsauer.com.

KEEP READING: More on Photography

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©