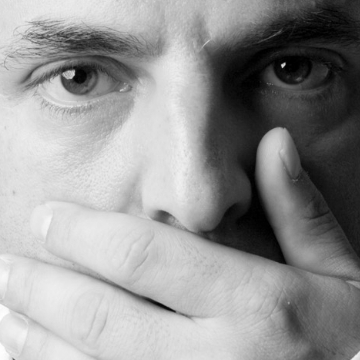

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges, the blind Argentine writer known internationally as the master of miniaturist short stories filled with labyrinths and mirrors, rose to prominence outside of Latin America during the 1960s. He split the 1961 Prix International with Samuel Beckett, bringing him initial attention. In 1962, English translations of two of his major collections of short stories appeared, Ficciones and Labyrinths, bringing him even wider readership. The “Latin American Boom” of Latino writers in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the success of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude brought still further interest to Borges’s work.

While Borges remains best known outside of Latin America for his fiction, inside Latin America, it is sometimes said his nonfiction essays are his strongest works. If Borges’s fiction totals 1,000 pages, his nonfiction totals that several times over. He wrote film and book reviews, book prologues, essays on social events and philosophical ideas, as well as biographies of modern writers. He also published hundreds of articles on Argentine literature and culture — the tango, folklore, literature, national politics.

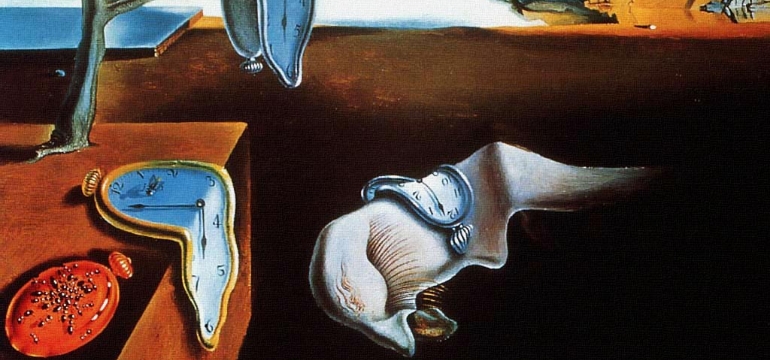

It is here in his nonfiction essays that Borges elaborates on the ideas that propel his short stories. It is here that he critiqued the various translations of The Thousand and One Nights, pondered the duration of Hell and wrote a history of angels. It is also here that Borges ridiculed racism and nationalism and took aggressive stands against anti-Semitism and the Nazis in an era of rising sympathy for fascists among the upper-classes in Argentina. The risks inherent in writing these articles in that milieu can be seen in the consequences: Borges’s support of the Allies lead Argentine President Juan Perón and his administration to “promote” Borges from his government position at the Miguel Cané Library to official Inspector of Poultry and Rabbits in the Córdoba municipal market, in effect forcing him to resign from government service.

His earliest nonfiction essays from the 1920s are close to impenetrable, and Borges himself disowned them, attempting to buy up all copies of the three original books that compiled the work from this early era and refusing to let them be republished during his lifetime except for selections in a French translation. Their importance is in suggesting the themes that Borges would develop during the rest of his career. In the 1930s, Borges began to simplify and polish his style, and also to publish regularly in newspapers and magazines. Borges spent three years as a writer for El Hogar, a woman’s journal, publishing a piece every two weeks.

Borges’s most important period of nonfiction writing begins in 1932 with the publication of Discusión and ends in 1956 with the arrival of his complete blindness, a fertile period of essays, book prologues, as well as book and movie reviews. After his blindness, Borges mostly wrote poetry because he could compose it in his head, but he also continued to write numerous book prologues and to give interviews and lectures in which he would talk spontaneously on subjects that would later be written down and included as part of his nonfiction work.

In his nonfiction, Borges shows not only his overwhelming and well-known erudition, but also his humor. In “The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights” he writes, “Orientalism, which seems frugal to us now, was bedazzling to men who took snuff and composed tragedies in five acts.” In a review of the movie Now Voyager, he describes Bette Davis as “weighed down by a pair of sunglasses and a domineering mother.”

He even more frequently exhibits his ability to obliterate others in an almost offhanded line or two. His starts his review of the film The Man and the Beast by writing, “Hollywood has defamed, for the third time, Robert Louis Stevenson. In Argentina the title of this defamation is El hombre y la bestia [The Man and the Beast] and it has been perpetrated by Victor Flemming, who repeats with ill-fated fidelity the aesthetic and moral errors of Mamoulian’s version — or perversion.” Borges remarks that in T.S. Eliot’s early poems and essays, “The influence of Laforgue is apparent, and sometimes fatal.” On Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage Borges writes, “Skillful photography, clumsy filmmaking — these are my indifferent opinions ‘inspired’ by Hitchcock’s latest film.”

Interested in reading these works in their entirety? Selected Non-Fictions edited by Eliot Weinberger and published by Penguin Books is a great place to start.

Tom Griggs is a photographer, writer, editor and educator based in Medellín, Colombia. He teaches between several universities and runs the site Fototazo.

KEEP READING: More on Nonfiction

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK AND PINTEREST.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©