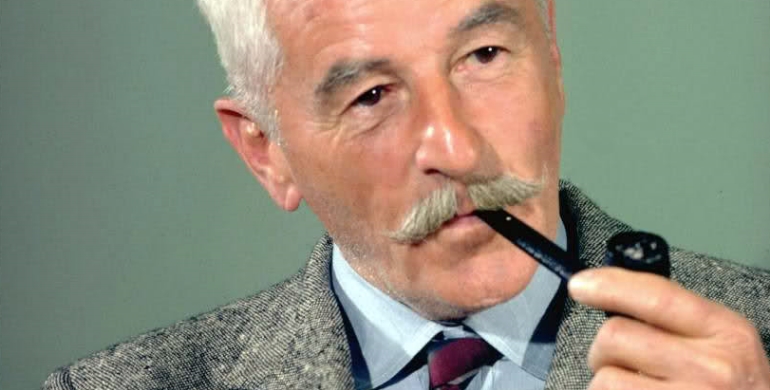

Etgar Keret (via EK News)

Just a day into my trip in Israel, on the way to Tel Aviv, I was informed that it was a time of great sadness: Three Israeli boys who had been kidnapped weeks prior were found dead; news of a young Palestinian boy burned alive soon followed. It was heartbreaking; it was anxiety-inducing. Rockets were being fired, and my family and friends were emailing constantly, worried that the escalating violence would come my way. I returned home to Brooklyn on July 7, shortly before flights were grounded and people were hiding out in bomb shelters.

After getting back, I followed the news more than usual. I became obsessed with the conflict between Palestine and Israel, reading every perspective possible, trying not to avoid the news out of fear that it would be too uncomfortable. I read articles and essays out loud to my boyfriend in our studio apartment. I followed all the links on Facebook, even the blatantly biased ones with declarations like “THIS IS PERSONAL.” I watched people take sides, make generalizations, name enemies.

In the novel Still Life with Woodpecker, Tom Robbins writes: “Poetry, the best of it, is lunar and is concerned with the essential insanities. Journalism is solar (there are numerous newspapers named The Sun, none called The Moon) and is devoted to the inessential.” There’s no doubt that news is vital, but there’s something to be said when it boils down to taking sides, declaring enemies and, especially, refusing those so-called “essential insanities.”

This weekend, The New Yorker published “Israel’s Other War” by the Israeli fiction writer Etgar Keret. In the op-ed, Keret addresses the motto “Let the I.D.F. win,” used by supporters of the Israel Defense Force to silence opposition from fellow Israelis. The author points out the flawed logic of the slogan and calls for greater tolerance of criticism within Israeli society — but even writing that, he notes, comes with an inherent risk: “Many people tried to convince me not to publish this piece. ‘You have a little boy,’ one of my friends told me last night. ‘Sometimes it’s better to be smart than to be right.’”

But this is what happens when fiction writers put their experience, their craft, their heart into the news:

On August 10, 2006, near the end of the Second Lebanon War, the writers Amos Oz, A. B. Yehoshua and David Grossman held a press conference in which they urged the government to reach an immediate ceasefire. I was in a taxi and heard the report on the radio. The driver said, “What do those pieces of shit want, huh? They don’t like the Hezbollah suffering? These assholes want nothing more than to hate our country.” Five days later, David Grossman buried his son in the military plot at the Mount Herzl cemetery. Apparently that “piece of shit” wanted a few other things than to hate this country. Most importantly, he wanted his son, like so many other young men who were killed in those last, superfluous days of fighting, to come home alive.

Fiction writers observe human behavior and lend it insightful commentary, remarkable clarity. Sometimes it feels much closer to psychology than anything else. Though it may be dangerous, it forces us to wrestle with the realities that evade “solar” journalism and to discover those nocturnal “essential insanities,” like the one Keret captures in the lines: "It turns out that this bloody road we walk from operation to operation is not as cyclical as we may have once thought. This road is not a circle, it’s a downward spiral, leading to new lows.”

I had a history teacher in high school who never told us his political standpoint on anything, instead telling us to observe, to look at every point of view, every risk people make in speaking. I’m not going to say where I stand on what Keret has written — that isn’t important. What is important is the heart behind an essay like his, the risk. Fiction writers may not be journalists, but we need more news with heart. We need humanity from writers themselves just as much as we need it from their stories.

Freddie Moore is a Brooklyn-based writer. Her full name is Winifred, and her writing has appeared in The Paris Review Daily and The Huffington Post. As a former cheesemonger, she’s a big-time foodie who knows her cheese. Follow her on Twitter: @moorefreddie

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©