Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T. S. Eliot (via Flickr)

One of the 20th century’s major poets provides keen insight into proper feline monikers.

Some might say that the naming of cats is a frivolous subject, but no less an exalted personage than T. S. Eliot has written extensively on the topic. The poet was a pioneer in cat-naming, and his contributions to the field inspired the 1981 musical Cats, to the delight/dismay of many. From Eliot's poetry collection Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, the poem “The Naming of Cats” begins:

The Naming of Cats is a difficult matter,

It isn't just one of your holiday games;

You may think at first I'm as mad as a hatter

When I tell you, a cat must have THREE DIFFERENT NAMES.

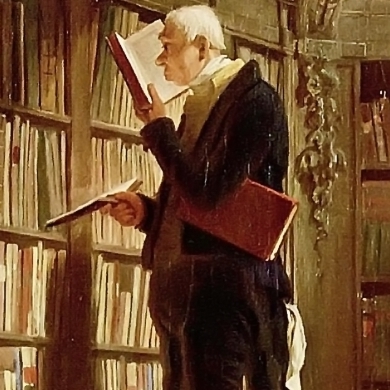

Eliot, 1934 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The science behind feline monikers has since been neglected, but recent innovations in technology demand we revive it with all of the resources and scrutiny our modern age has to offer.

Thankfully, some scientific inquiry into cat-naming is already underway. A 2013 experiment conducted by researchers from the University of Tokyo tested 20 house cats, playing for them recordings of strangers and their owners calling their names, and gauging the animals’ reactions. What they discovered was that cats are readily able to recognize their owners calling their names, but that they refuse to come in any case.

“These results indicate that cats do not actively respond with communicative behavior to owners who are calling them from out of sight, even though they can distinguish their owners’ voices,” write researchers Atsuko Saito and Kazutaka Shinozuka.

Note the researchers’ puzzlement. Obviously they are unfamiliar with basic cat etiquette. Cats do not wait breathlessly to fulfill your every cat-related desire. (They are not dogs!) Any cat owner in history could have explained this without going through all the bother of recordings and testings and observations, but at least now we have scientific evidence supporting the notion that cats don’t give a fuck what humans want.

Further feline research is also on its way. With lightweight cameras and GPS tracking, scientists now have the tools necessary to solve the eternal mystery of what the hell it is that cats do all day. Cat Tracker is currently enlisting the aid of pet owners to gather data on their cats’ movement, diet and health. The aspect of this project most relevant to us is brought up by Smithsonian.com: “If you are concerned about your cat's privacy, you can have the data published under a cat alias.” We are right back to T. S. Eliot.

The poet, despite his own admirable work, recognized the futility of all human endeavours in the field of feline monikers. After explaining the nature of cats’ first names (familial) and their second ones (particular) in “The Naming of Cats,” he attempted at last to address the mystery of each cat’s third name:

… above and beyond there’s still one name left over,

And that is the name that you never will guess;

The name that no human research can discover —

But THE CAT HIMSELF KNOWS, and will never confess.

When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name:

His ineffable effable

Effanineffable

Deep and inscrutable singular Name.

Kathleen Cooper is a writer in Virginia who writes about books, history, sewing and feminism, among other things. She has had many cats, none of whom come when they are called.

KEEP READING: More on Science

![Eat Prey Drug: The Hollow Earth [NSFW]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/507dba43c4aabcfd2216a447/1408211766316-TBR0CIM1IWX4GAX25D2J/image-asset.jpeg)

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©