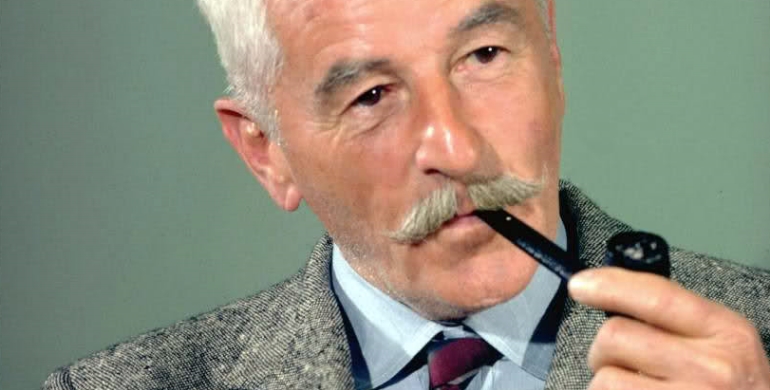

William Faulkner (via Wikimedia Commons)

Hailed as a masterpiece today, The Sound and the Fury was initially written off by the public and the author himself. Why?

“It was the most splendid failure” is one William Faulkner’s most famous remarks about The Sound and the Fury. When he began what may be his most important work, he set out with the intention of bringing to life a singular moment around which an entire family history is born: the muddied drawers of a little girl, Caddy Compson, becoming visible to each of her brothers as she climbs a pear tree to look in on her grandfather’s funeral. Faulkner saw Caddy as a doomed child, and in presenting her tragedy and the tragedy of all the Compsons, The Sound and the Fury was received at the time — 1929 — as both “unique and distinguished” and “deliberately obscure and considerably incoherent.”

First edition cover of The Sound and the Fury (via Library of Congress)

Clearly, time has been kind Faulkner. There are now few who would dispute the notion of The Sound and the Fury being nothing short of a masterpiece. Faulkner was certainly not the first to employ a stream-of-consciousness narrative, but his use is among those most frequently held up for its brilliance. This, along with his experimental telling of the story over four sections with four different narrators, was daring for an author who had not yet enjoyed much financial success (though there had been some critical praise).

The Sound and the Fury was a “splendid failure,” according to Faulkner, because he had first tried to tell the story through Benjy and, failing at that, attempted again through Quentin, then once more through Jason. Unsuccessful with all of the Compson brothers, he tried one last time to tell the story himself, only to fail for the fourth time.

Yet, despite this self-deprecation, there was no lack of hubris on Faulkner’s part when he delivered the manuscript to Ben Wasson, his literary agent at the time. According to Wasson:

[Faulkner] didn’t greet me with his softly spoken “good morning” but merely tossed a large obviously filled envelope on the bed. “Read this one, Bud,” he said. “It’s a real son of a bitch.”

I removed the manuscript and read the title on the first page: The Sound and the Fury.

“This one’s the greatest I’ll ever write. Just read it,” he said, and abruptly left.

Indeed, Faulkner’s persistence during the early stages of publishing The Sound and the Fury is the main reason that it exists as it does today. He was scathing in letters to those (including Wasson) who tried to exert creative control over his work, doing all he could to ensure that punctuation was left out where he intended, that the italicized sections remained unchanged and that his narrative structure was completely preserved.

Faulkner’s typewriter (via Flickr)

Writers can perhaps benefit from similar persistence, but it’s more important to recognize the value of the risks Faulkner took with The Sound and the Fury. He put considerable time and effort into the writing process, utilizing innovative techniques that contributed to a changing literary landscape. Rather than following the status quo and producing something that he knew would be published and likely earn him greater financial rewards, Faulkner instead devoted himself to creating something that wouldn’t cater to publishers or audiences. He wrote free from worry over sales, taking risks in telling his story that he felt were necessary to the story itself.

For the introduction to a new edition of The Sound and the Fury — which was never published during his lifetime — Faulkner spoke of his writing process and the freedom he enjoyed:

When I began the book, I had no plan at all. I wasn’t even writing a book. Previous to it I had written three novels, with progressively decreasing ease and pleasure, and reward or emolument. … One day it suddenly seemed as if a door had clapped silently and forever to between me and all publishers’ addresses and booklists and I said to myself, Now I can write. Now I can just write.

J. Francis Wolfe is a freelance writer and a noted dreamer of dreams. He aspires to one day live in a cave high in the mountains where he can write poetry no one will ever see.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK AND TUMBLR.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©