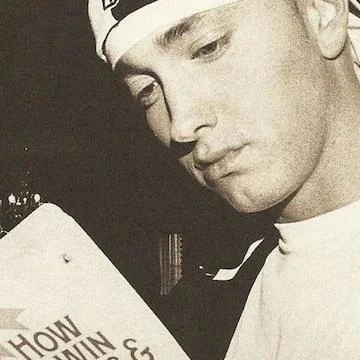

Anthony D’Amato (via Shore Fire Media)

Anthony D’Amato’s new album, The Shipwreck from the Shore, brings back a sound thought lost.

On the banks of the river where they found me

caked in mud with a canteen by my side,

There was nothing left that could identify me

on the banks of the river where I died.

— “On the Banks of the River Where I Died” by Anthony D’Amato

The kid on stage, who dedicated his song to Woodie Guthrie, was a 27-year-old from New Jersey. His scruff, long hair, plaid shirt and boots made him look like a Brooklyn hipster or the artsy Ivy League types at Princeton, where he went to college. His sad voice may have sounded more like our generation’s Conor Oberst than like Guthrie's, but he was channeling old spirits. His singing conjured the ghost of old Greenwich Village back to life.

Long before that Wednesday at the Bowery Electric, the feeling of the Village was familiar to me. I found it as a teenager in Virginia a decade ago on records by Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk and Townes Van Zandt. Since I moved to New York a year ago, I'd been looking for what I thought was a lost world.

We've all been there exactly once. When it happened to me I was 23, peddling a bike in western Japan past the bare November rice paddies to the school where I taught English. A week after a Skype call to Philadelphia, I realized she and I were done. Her new med school was a foreign place, she a foreign person.

Six years later, a song sent me back: “After all this time it's strange to think, I could say her name and feel nothing.” So went the lyric to “If It Don’t Work Out” by folk-rock songwriter Anthony D’Amato. On the G train, as I heard the song for the first time on my way to the office, I was suddenly 23 again: “Oh to find love once, oh to find love once. My god, I thought it would be enough, just to find love once.”

Songs about heartbreak, earnest with an edge of humor, are what folk blues does best. Most of the songs I had in Japan were by Dylan, Oberst and The Magnetic Fields — "Don't Think Twice, It's Alright," "Take It Easy (Love Nothing)" and "I Don’t Really Love You Anymore." These songs work the same catharsis that all the best literature does: They make us feel we're not alone.

The Shipwreck from the Shore by Anthony D’Amato (via Shore Fire Media)

This is just what happens on The Shipwreck from the Shore, D'Amato’s major label debut released earlier this month. The album could have been a novel about a young man looking back at his first love's end from the safe distance of "the shore,” except that it gets its scenes and emotion through pointed lyrics. As the title line of one song on Shipwreck goes: “You take the bed and I'll take the couch, if it don't work out.”

Lest you expect a breakup album to be angry or depressive, The Shipwreck from the Shore is not. Moods range from nostalgia to irony, but never bitterness. The tracks follow a careful balance of feeling, from upbeat release through the conflicted desire to comfort a person you once loved but now have to hurt. The album's opening track, "Was a Time," is rousing, with quick drumbeats, thick layers of electric fuzz and harmonica. Embedded, though, in the song's enthusiasm — an energy that hints to us that our narrator is the one who did the leaving, not the one left behind — is a mood less upbeat but familiar to anyone older than 25:

There was a time when I could weather the raging of the storm,

There was a time when I could gather the roses from the thorns,

A time when I was certain, a time when I was sure,

There was a time that I loved you, I don't love you anymore.

As I listened to D'Amato at the Bowery Electric, I felt the surge you get when hearing something new while recognizing where it’s taking you. There may have been kids my brothers' age bobbing in the crowd, but if you closed your eyes and listened to D'Amato sing and play, a row of old records came to mind: The Freewheeling Bob Dylan; Inside Dave Van Ronk; I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning — a shelf of favorites.

When I imagined Greenwich Village at 17, it was wrapped up with music and poetry, travel and novels, bebop and beatniks and blues. It was where Paul Curreri, the

Virginia-born songwriter my friends and I followed, went to play his music infused with Van Ronk-style finger-picking and the talky poetry of Frank O'Hara. Curreri's father was law partners with my best friend's dad, so the songwriter’s transformation from a boyhood soccer player in suburban Richmond to a globe-trotting artist made such a metamorphosis seem possible for me too. “There ain't crossing nothing sweeter,” Curreri sung, “than the ‘keep out’ of the theater. Lift that velvet rope, now lift it for me.” The place where ropes got crossed, I always imagined, was Greenwich Village.

The Village was where creative people came to be reborn — that’s what I believed while listening to folk and blues records on my suburban childhood bed, reading Salinger novels and fantasizing of becoming a writer. Greenwich Village was where a Jewish 20-year-old from Minnesota, inspired by black blues men from the Mississippi Delta, Dust Bowl-era protest singers and the Welsh poet who had written “Do not go gentle into that good night” became Bob Dylan. It was where Billie Holiday sang "Solitude" and Van Ronk crooned "Hang Me, Oh Hang Me," having migrated from nearby Brooklyn but also far across time and race and space back to the black ragtime of 1920s New Orleans and the down home blues of Mississippi John Hurt.

Long before Paul Curreri followed the gravity of downtown Manhattan up from Virginia, this was where Ginsberg met the best minds of his generation, where Kerouac found the people for him were the mad ones. Home of the Village Vanguard, it was where Charlie “Yardbird” Parker, a black boy from Kansas City, transformed jazz in the ‘40s. Birdland, the club named after him, was my first exposure to New York, when I came with college friends to hear pianist Brad Mehldau, the Bad Plus and McCoy Tyner. But where was the folk music?

D’Amato (via Facebook)

Anthony D'Amato has merged himself with the Village of old. His lyrics bring to mind less rock musicians than poet bards, like Paul Muldoon, Pulitzer Prize winner, New Yorker poetry editor and D'Amato's college mentor. The songs mine timeless themes — loss of youth, fear of death, hopeless want — and the existential ones we're all heirs to: the vanity of ambition, the risk in trust, the tragic stakes inherent in hope.

These moods have resonance beyond this patch of New York, of course. The blues were born from American history — out of slavery, racial strife in the deep south, the progressive activism of the Dust Bowl and the ‘60s — but they're also universal. They have the tragic frequency of Oedipus Rex and Hamlet and The Sound and the Fury. “I'm hoping to be handsome when I'm stripped of all my meat,” D'Amato sings in “But for You,” a song from his 2012 release Paperback Bones. That universality, the melting into a culture timeless and global, is what so many come to New York to find.

What the best folk does is break barriers. You hear someone like D'Amato, like Billie Holiday singing "Solitude," and you see you've got company. Never solo in the hunger that won't leave us while we're mortal — the human condition, spirit of the blues.

Sure feels good to hear it sung again.

Taylor Beck writes for GQ, Fast Company and other magazines in New York. He was once a dream researcher in Kyoto, a teacher in rural Japan and a neuroscience flunky in labs from Princeton to St. Louis. He agrees with David Foster Wallace that reading is the best way out of a skull-shaped cage, and with both The Flaming Lips and Copernicus that we are floating in space.

KEEP READING: More on Music

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

![The Rip Van Winkle of Punk [NSFW]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/507dba43c4aabcfd2216a447/1404137063331-A07C54MCRBO7F7AD1CC5/spike10.jpg)

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©