Flavorpill’s list of cryptic book titles—including the just released HHhH, which got my bloggin' buddy James all infranovelistic, and last year’s C—brought to mind the Diagram Prize, which is awarded yearly to books with the strangest titles. Sometimes the quirk isn’t just contorted syntax or the result of concision; sometimes it's more about semantic friction, when a literal meaning scrapes up against your capacity to make sense. Like last year’s Diagram winner: Cooking with Poo. (Just in case you wondered, Poo ain’t shit.)

Presumably the publisher hoped to cash in on our confusion. After all, titles have to pop. And publishers serve two masters: commerce andcreativity, profit and art. Titles have to be memorable enough to stick with readers, yet clever enough to intrigue tastemakers. No easy task. Try too hard and you end up with something like House of Leaves. Do you get it? The house is really the book, cuz pages can be called leaves! Oh man, so clever! That one, at least to my ears, is a little too proud of its punning. Yet here I am, discussing it.

Others titles have impressed me more. Here's a list of some of my favorites, and what I think makes them work.

- The Crying of Lot 49. Thomas Pynchon’s slightly paranoid novella has stuck in my brain since I first glimpsed its title. It must be that howling gerund with its long i sound and suggestions of pain. And then there’s the title’s sonorous quality. It begs to be spoken aloud. Try it a couple times. Really.

- Euonia. Okay, basically this title banks on obscurity. You probably hadn’t heard the word “euonia” before you heard about this book. It means “beautiful thinking.” It’s also the shortest word in English that contains all the vowels, which makes it a particularly fitting title for Christian Bök’s exercise in constrained writing. Each of the book’s five chapters uses only one vowel, beginning with a, ending with u. The book is a striking thing to read, especially the guttural u chapter.

- Life A User’s Manual. The intricate phenomenological descriptions that George Perec composed for this book—each chapter describing a single room in the apartment building where the protagonist, a recently deceased guy who liked jigsaw puzzles, lived—aren’t exactly what you’d expect to find in a typical user’s manual, but this is life, not a screwdriver. The title sticks with you because most novelists (not to mention most publishers) don’t have the nerve to put a technical sounding title on their novels; such a thing might dissuade impulse buyers.

- Watership Down. Amazing use of ambiguity here: you don’t really think of Watership Down, the hill, when you first read it. Instead, you picture a curious seafaring vessel, "down" as in sunk or in the process of going down. Then you read about rabbits and "hrair limits" and it all begins to make a bit more sense. But at that point, you’ve already been led down the garden path, and the title is ensconced in your memory.

Those titles are solid enough to serve both art and commerce, I think. Of course, I doubt they’re as brilliant as my idea for a novel concerning self-motivating punctuation marks. The title's not gonna be written out but set with the interrobang glyph. I'll let the critics argue about how to pronounce it. And yeah, the gimmick is that the narrator's deployment of punctuation marks evolves as her narrative unwinds. it'll be nigh unreadable, but oh so punny and witty. Beat that, internets.

Image: flickr user GardenofEdits

In Granta, Jaspreet Singh recently described how her mother, in translating the daughter’s book from English to Punjabi, “preserved the emotional impact” of the fourteen stories she had written, up until the final piece, which read very differently.

My mother translated the story I never wrote...This new fourteenth story was my mother’s story and not mine. No translator, no one has a right to change my story, I thought. Not even my mother.

It is a strange and unsettling thought that a translator might deliberately or, worse, unconsciously present us with a story only tangentially related to the original-language text. But what, exactly, do we feel if we realize that we've read a false or unfaithful translation? Loss? Rage? What exactly have we lost, if we cannot read the original, and where should we direct our anger, if we have been given something that otherwise we would not have had at all?

Translation is the last remaining vestige of rewriting; it is a career not unlike that of being a scribe in medieval times or a typist in the twentieth century. “There’s nothing glamorous about it,” my friend said of working as a translator at UNESCO in Paris. “I switch the words from French to English, make sure it sounds logical, and then pass it on to my reviser.”

Readers (and even editors!) often assume that a fluid translation is accurate, and reviewers consistently declare English-language books from abroad "ably translated," without much thought given to the underlying process. Even when the translation is read and annotated by the publisher, questions about the text are usually posed to the translator, rather than being answered by looking at the original. So rogue translations are all the more discomfiting when their dissemblances are discovered.

If the rewriting Jaspreet Singh’s mother performed feels like theft, then where do you draw the line between transducing something and traducing it? Are all translators thieves?

I detest the Italian adage “traduttore, traditore” ("translator, traitor" would be the most literal rendering). There is something available now in the target language whereas previously there had been nothing. That is no betrayal; indeed, it’s a gift. Sometimes the translation is for the better, as when writers like Paul Auster find themselves more famous abroad than at home. Really, attempting to moralize this recalls the recent (and inconclusive) brouhaha over facts and truth in John D’Agata and Jim Fingal’s The Lifespan of a Fact.

I don’t think a question so polarizing can be answered, and the futility of the thought itself only merits satire—as in this piece from Dezső Kosztolányi’s Kornél Esti, translated by Bernard Adams, about a kleptomaniac translator:

In the course of translation our misguided colleague had, illegally and improperly, appropriated from the English text £1,579,251, together with 177 gold rings, 947 pearl necklaces, 181 pocket watches, 309 earrings, and 435 suitcases...Where did he put these chattels and real estate, which, after all, existed only on paper, in the realm of the imagination, and what was his purpose in stealing them?

image credit: Igor Kopelnitsky, corbisimages.com

HHhH, Laurent Binet's account of the assassination of a top-ranking Nazi in 1942, is divided into 257 mini-chapters. In an attempt to comprehend Binet's layering of fact and fiction, as well as the totally incomprehensible era he describes, I'm going to try out his "infranovel" techniques myself.

Read More

Forget what Kayla B. wrote about book trailers. (You kiss your mother with that mouth, Kayla?) Check out the new promo for our spring title, Louise: Amended, and find out why our March theme is "Demon Wrestlers." Happy viewing!

Read More

Since passing in 2003, Roberto Bolaño has published a lot of books, probably more than you or I will put out in our combined afterlives. Because once you get famous—and you must be pretty famous if Heidi Julavits and other lit bigwigs are singing your praises at Galapagos—it’s not just your finished work that attracts readerly eyes. Some greedy fans will find the time to scrutinize marginal notes in your correspondence or drafts and sketches taken from your computer. When it comes to Bolaño, I am one of those eager gleaners; I have been ever since The Savage Detectives made me regret my somewhat sensible (read: mostly boring) life and pine for those of its voluntarily down-and-out (read: awesomely authentic) characters.

So I was excited about The Secret of Evil, the latest of Bolaño’s work to be translated into English. It’s a collection of “stories,” though it contains some of the putatively autobiographical work released last year in Between Parentheses (including a favorite of mine, “Beach,” the account of a recovering dope addict—perhaps Bolaño, perhaps not). That The Secret of Evil draws from the previous book is suggested even in its design: Evil has a blind embossed set of horns on its dust jacket, recalling, in invisible tactility, the foil-stamped parentheses on the cover of the former collection. Clever clever.

I’ve invested a lot of time both in Bolaño and Arturo Belano, the former's fictionalized self. But what about you non-fanatics? What would you think of the The Secret of Evil? It’s a solid collection of stories, sure, but some of them are hard to appreciate without the rest of Bolaño’s writings there in the background. And unlike, say, 2666, this was in no way close to being finalized for print.

Evil also marks a turning point in the way we pilfer dead authors’ “papers.” Its introduction goes into some detail about how the pieces were taken from Bolaño’s computer, going so far as to name the files it drew from. Hard-copy drafts are probably a thing of the past. The next thing to disappear may be the locally stored digital file; instead, all our manuscripts will be up in the cloud. And, of course, letters: they’re dead, and we're sure to see more and more volumes of email correspondence.

What's next? Maybe writerly Twitter and Facebook accounts will be combined with smartphone GPS logs—along with, we gotta hope, those of the writer's spouse, friends, publishers, fuckbuddies, etc.—and published as an app. Then future academics will make observations like this: "It appears that Rushdie was more prolific in the days he spent with Lakshmi than when he was when he was about town with Lieskovsky. I will use this dataset to to construct an algorithm that rates muses like Klout does social media yuppies."

The digitization of everything is gonna make for exciting, horrifying stuff, people. Just hope you don't become famous. Because if you do, you will have no secrets, no secrets at all.

Image: flickr user Kleiber Fragoso

Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century, brilliantly translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia, is out from FSG this week. In it, a translator and all-around dandy finds himself romancing a beautiful (and already engaged) woman in the "moving city" of Wandernburg, Germany. All the while, he attends salons to debate about art, philosophy, and other questions of the nineteenth century, and wonders how to escape from the ever-shifting locale.

It occured to me that Wandernburg is the latest in a long lineage of uncharted territories, so I've put together a brief history—from Laputa to Lost.

Laputa, from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

"The reader can hardly conceive my astonishment, to behold an island in the air, inhabited by men, who were able (as it should seem) to raise or sink, or put it into progressive motion, as they pleased...it advanced nearer, and I could see the sides of it encompassed with several gradations of galleries, and stairs, at certain intervals, to descend from one to the other. In the lowest gallery, I beheld some people fishing with long angling rods, and others looking on."

In the third book of Gulliver's Travels, Swift satirizes the stormy relationship between England and Ireland as a large landmass and an airborne island. The latter, which also satirizes the Royal Society, boasts such eccentricities as "a shoulder of mutton cut into an equilateral triangle" and workers "softening marble, for pillows and pin-cushions."

Lincoln Island, from Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island

"The balloon, which the wind still drove towards the southwest, had since daybreak gone a considerable distance, which might be reckoned by hundreds of miles, and a tolerably high land had, in fact, appeared in that direction...They were ignorant of what it was, whether an island or a continent, for they did not know to what part of the world the hurricane had driven them. But they must reach this land, whether inhabited or desolate, whether hospitable or not."

After a disastrous balloon flight, a group of explorers lands on a deserted island somewhere in the South Pacific, and—in line with Jules Verne's boundless optimism—makes buildings out of bricks and even constructs an electric telegraph. However, the island abounds with mysteries (such as a pig with a bullet in it) and the group must figure out where the other humans are, if there are any at all.

The city Earth, from Christopher Priest’s Inverted World

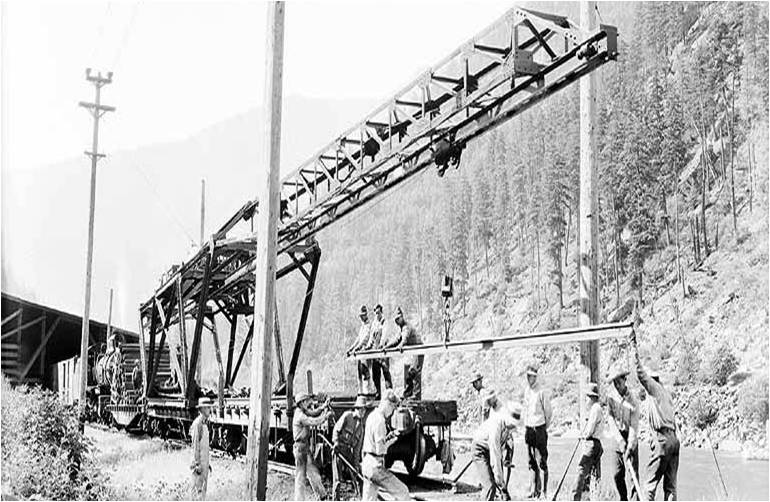

"[I]t was clear that the rest of the tracks led along a downhill gradient. In due course the final pulley was removed, and all five cables were once again taut. There was a short wait until, at a signal from the Traction man at the stays, the slow progress of the city continued…down the slope towards us. Contrary to what I had imagined, the city did not run smoothly of its own accord on the advantageous gradient. By the evidence of what I saw the cables were still taut; the city was still having to pull itself."

"Earth" in this science-fiction novel refers not to a planet but to a city that moves on tracks at a controlled rate toward an unknown destination. Hundreds of guildsmen must lay tracks ahead of the gigantic structure, and remove the tracks that have already been crossed. In this strange universe, distance literally becomes time—"I had reached the age of six hundred and fifty miles" is the first line—and the ramifications of this city's perpetual movement into the future become increasingly bizarre.

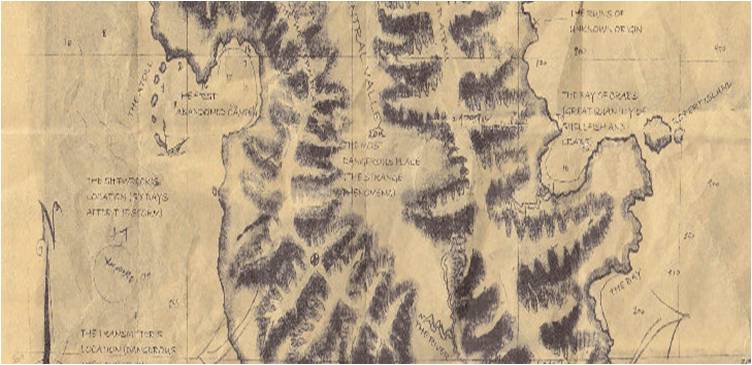

The Island, from Lost

"I've looked into the eye of this island, and what I saw was beautiful." —Locke

When an airplane going from Sydney to Los Angeles crashes on an island in the South Pacific, survival is the first aim of the marooned travelers. But this TV show, which owes an obvious debt to Jules Verne's earlier island, slowly reveals bizarre phenomena—Arctic polar bears, a metal hatch in the jungle's ground—and suggests a very a disturbing reality. The show itself becomes increasingly disorienting, switching from flashbacks and flash-forwards to flash-sideways storylines as it becomes clear that the island can move in time as well as space.

Wandernburg, from Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century

"Wandernburg: moving city, sit. approx. between ancient states of Saxony and Prussia. Cap. of ancient principality of same name...Despite accounts of chroniclers and travellers, precise loc. unknown."

In comparison to these other fantastical inventions, Andrés Neuman’s uncharted city seems positively pedestrian. Although storefronts and streets switch positions overnight, the city as a whole remains relatively moored on land: Hans, the eponymous traveler, is able to send mail to and from various cities in Europe. The focus is less on an isolated space in the world than on an isolated space in the philosophy and intellectual discourse of the nineteenth century. As Hans sits between two countries, so he translates between many languages and the novel itself melds the details of nineteenth-century doorstops with twenty-first-century novelistic techniques. The result is an enthralling epic of a man who bridges gaps of all sorts while looking, always, toward the future.

Image credits: Gulliver beholding Laputa, wikipedia.org; Laputa map, books.google.com; Mysterious Island map, verne.garmtdevries.nl; Great Northern Railway track-laying image, lib.washington.edu; Lost island map, lostified.com; Andrés Neuman photo, nutopia2sergiofalcone.blogspot.com

Whenever I hear about The Great Gatsby, my mind shuttles to a passage of Haruki Murakami's Norwegian Wood, one of my oft-read favorite novels. Like me, the protagonist Toru is a serious rereader: “This is my third time through [Gatsby], and every time I find something new that I like even more than the last time.” So it's not too surprising that The Millions (and a linkedGuardian article) posits The Great Gatsby as the most “rereadable” fiction. Since my rereading habits tend to change with the seasons, let me offer a few recommendations for winter nesting, summer tanning, astral projecting, and more.

• Cocooning for the winter: I plowed through Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Idiot and Crime and Punishment in a chair next my studio's radiator, where the hiss and clatter of pipes covered whatever music was playing the background. To me, they're the most cold-weather appropriate of this Russian's enveloping oeuvre.

• Beach jaunts: Thomas Mann's Death in Venice radiates with dry summer heat and soothing Adriatic air, and its novella length is perfect for beach reading (tack on 45 minutes for the Nassau County train ride). Dostoevsky's short novel The Gambler is another warm-weather favorite—and I'm admittedly smitten with Mlle Blanche de Cominges.

• Emotional inspiration, in brief: Anton Chekhov's short stories never fail me. “The Huntsman,” “Anyuta,” and “The Black Monk” are major tearjerkers—and with Chekhov's unbelievable gift for brevity, “The Huntsman” achieves this over barely four pages. I share these with girls to show them that I am a sensitive dude.

• Emotional inspiration, long read: Zadie Smith's The Autograph Man...and yes, I love White Teeth as well. I met Smith at a reading back when The Autograph Man debuted (she read the prologue, another significant tearjerker), and I've returned to her idiosyncratic second novel ever since.

• Far East escapism: Haruki Murakami's pop psychedelic The Windup Bird Chronicle. I've written about this before for Black Balloon, and it's my go-to for getting “away." Plus, Dance, Dance, Dance is one heady trip (psychic teenagers and talking sheep, anyone?).

• Even farther (like another universe) escapism: Douglas Adams' The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, or as the subheading reads: “five novels in one outrageous volume.” I tend to tucker out at So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, but it's still a stellar ticket outta here. Towel not included.

For my fellow rereaders, I close with a helpful tip. See, my Manhattan studio couldn't accommodate a proper library, but my reading habits demanded one. To combat my finite space, I read and re-read certain novels until I'd exhausted them, and then I shipped them back to my parents so I could buy more.

But the Murakamis, the Russians, Zadie...those I made room for. Who needs a bathtub, anyway?

Image courtesy the author

Arielle Zibrak’s "Super Short Cliff’s Notes for All Classic Novels," a McScweeney’s list that I strongly encourage you all to read, inspired me to come up with some Cliff's Notes of my own. Yes, this is just for fun, but I also like the play of structure, seeing what happens when we look at complex things via a simplified frame. So let's summarize a few things that shouldn't be summarized!

Cliff’s Notes for Break-Ups

- You tell someone “It’s not you, it’s me.”

- Someone tells you “It’s not you, it’s me.”

- You sleep with this person

- Both parties drink excessively

Cliff’s Notes for Making Dinner

- You sauté onion and garlic in olive oil, add items

- Items taken from the freezer, boiled in water

- You call someone to bring items to you

- You stare into refrigerator until hunger becomes a mere mind state of your lesser body

Cliff’s Notes for Wizard Books

- There’s one guy without a sword

- Boobs

- The individual triumphs over society while saving society

- Boobs

Cliff’s Notes for Dating

- You introduce yourself, talk about stuff, make out

- You make out, introduce yourself, talk about stuff

- You fight while talking and making out

- Both parties are drunk

Cliff’s Notes for Commenting on the Web

- Utterly generic yet heartfelt encouragement indicated by exclamation point

- Personal attacks on author

- Comment section used as platform to plug own ideas/book/website

- Complete the phrase “That sure is _____” by copying and pasting a line from the article

Why not whip up your own Super Short Cliff's Notes? I left out "Leaving Afghanistan Responsibly" and "Hiding Your Porn" just for you. If you get stuck, simply remember Zibrak's final note: "Author was drunk."

image: worrylessenjoymore.com

When I was seven, I got Norton Juster's brainy adventure YA The Phantom Tollbooth as a present. I skipped past the maps to the first Jules Feiffer illustration of Milo. Then all of a sudden this unquestioning boy was piloting a toy car past a tollbooth and stopping in front of a Whether Man, debating whether there'll be weather.

I was hooked. I loved the idea of another world. I had dreams about watching Chroma's orchestra putting color into the world. And of course I'd be able to spell hard words like "vegetable" just as fast as the Spelling Bee.

I even liked the film version. (I know. I know.)

There's a really cool scene where Milo goes back and forth in the tollbooth, switching from human to cartoon to human. That was when I started seriously wondering what I would look like if I was cartoonified.

I told my dad about this idea while we were eating pie at Tippin's. And then my dad, the nuclear engineer, turned my world upside down: he told me to read Flatland. We went to the library, and my jaw dropped as I saw this picture of a sphere moving through a two-dimensional world:

Now over a century old, Flatland is the story of a Square living in a two-dimensional world: houses are their blueprints, and women, being lines, are required to hum as they move so that polygonal men aren't accidentally run through in their silence. The Square meets a Sphere one day, perceiving the three-dimensional being at first as a circle that expands and contracts at frightening speeds. Once the Square finally understands the third dimension, he tries in vain to convince the Sphere that there may be even higher ones.

It was a Copernican revolution of my mind. I imagined what an amoeba floating on the surface of a pool would see as an Olympic diver broke that surface: ten circles for fingers joining into two arms, a third circle for the head joining with the arms into an elongated torso...and then, my brain shifting in the opposite direction, I tried to imagine the fourth dimension.

Which I couldn't do. I saw drawings of hypercubes, and realized that they were exactly as useless as one-dimensional drawings of cubes. I couldn't get my head around the dimension extending outward from our world. My excitement faded. I didn't want to be cartoonified anymore.

I went back to The Phantom Tollbooth. In the end, Milo rescues the twin princesses Rhyme and Reason from the Castle in the Air. Then the entourage comes back and there's a great big festival before Milo heads back to his real world, no worse for the wear. It wasn't until much later that I laughed; I finally understood that even the three-dimensional world would make no sense without rhyme or reason.

Image: Alec Bings, the boy who sees through things, drawn by Jules Feiffer

Everybody knows Israelis are sexy. They’re all buff from years in the military, they can curse fluently in Hebrew and Arabic and English, and to top it off, they’re impossibly tan from living under the Mediterranean sun. I’m jealous of my friends who go to Tel Aviv in the summers and lounge on the beach with great eye candy, some Goldstar beer, and a few Israeli books.

Yep, books. Sayed Kashua’s Second Person Singular, which came out in Israel two years ago and is out in English now, had me turning the pages, wondering what sort of scandal might be going on under the protagonist’s nose.

The author is an Israeli Arab—a sizeable minority living in Israel—and it’s no surprise that his characters are similarly marginalized. When a rising Arab lawyer who has successfully become Israeli discovers a love letter from his wife to someone he doesn’t know (in a used bookstore, no less), he sets out to discover who the addressee is, and how this has all been happening without his knowledge. Needless to say, Israel’s a country that struggles withits identity and its survival, and the descriptions of the rift between Arab and Jewish cultures by one who straddles the divide are illuminating, frighteningly accurate, and deeply moving.

I kept thinking of an evening in college: I got to talking with a fellow freshman who had a hookah in his room and said he was from Jerusalem. When my friends and I walked out of his room that night, we saw the sign on his door with his name—just like the signs the freshman counselors had put on all the other doors—and his hometown. It said East Jerusalem, Palestine, but I paused when I saw he’d crossed out the Palestine and scrawled Israelunder it. From my side of the fence, I hadn't ever thought about the feelings Palestinians might have about this ongoing struggle.

Every so often I hear about bombings in Israel or Palestine or the territories in between (and, to put this in context, I hear about this just as often as I hear about murders or violent crimes on the local news). It's true that there are deep-rooted historical arguments for the divide between Jews and Arabs, between Israel and Palestine, but there's more to the story. In fact, they already do work together in spite of the ongoing conflict, making reality far less black-and-white than either side's rhetoric might suggest.

There’s a mystery to be unraveled in Second Person Singular, many mysteries in fact, but the biggest questions remain unanswered in the book’s pages. If I ever go back to Israel, I’ll go to Bat Yam with my surfboardand my eyes open. Behind those superficially shiny bodies are some astonishingly forceful sentiments about Israel, Palestine, and the people trapped in between.

image credit:flickr.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©