Something weighing you down? Why don't you come to Ayn Rand for help?

It may help you more than all those self-help books you got after graduating.

Though if one of those books happened to have a one-word title, you may want to give it a second chance.

Just don't go and feel entitled when your self-published one-word title fails to become a bestseller.

You don't want to find yourself turning into a psychotic fictional character over the ordeal.

Just try to calm down, perhaps by turning on some disco?

Don't be ashamed. Afterall, all writers have their own particular quirks.

Dan Brown's quirks are so hard-wired into his system that it can be explained via a handy flowchart.

Image source: USA Today

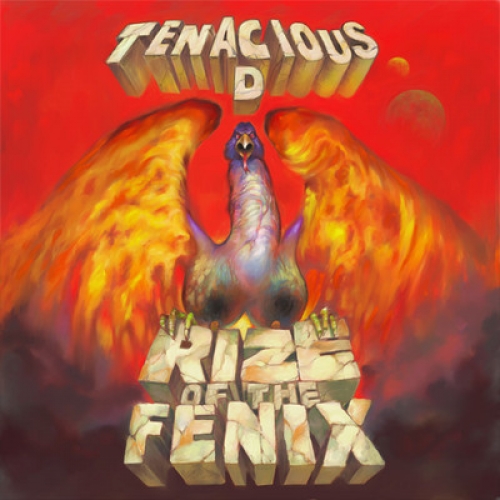

Nnnndude. To celebrate the release of Tenacious D's new album, Rize of the Fenix, here's a glossary of JB and Rage Cage-minted terms.

Read More

A Tyrannosaurus Rex [Tyrannosaurs baatar] skeleton ostensibly excavated in Mongolia, and allegedly illegally transported therefrom, was sold at auction on Sunday for just over a million dollars by Heritage Auctions of Dallas, Texas to an unnamed phone bidder. On June 19th and 20th, London will host the International Colloquy on the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, even as Greece teeters on the brink of withdrawing from the Euro-zone. Lord Byron graffitied his thoughts on national patrimony and plunder on a plaster wall at the Parthenon.

1.

“Before bidding on the skeleton began, the auctioneer announced that the sale would be ‘contingent upon a court proceeding dealing with this matter.’ Almost immediately, Robert Painter, a lawyer representing Elbegdorj Tsakhia, the president of Mongolia, stood up with a cell phone held to his ear and yelled, ‘I’m sorry, I need to interrupt this auction. I have a judge on the phone’ … Despite the ruckus, the auction continued, and the considerable artifact sold for $1,052,500, to an unidentified phone bidder. The small audience, slightly confused, applauded.”

—Laura L. Griffin, “T-Rex Wreck: Mongolian Representative Disrupts Skeleton Auction,” The New York Observer, 21 May, 2012.

2.

“The neo-fascists are hunting down immigrants in the middle of downtown Athens, in the streets north of the central Omonia Square. They call it cleansing. They hunt people like Massoud, a 25-year-old Afghan from Kabul. He has been living in Athens for five years without a residency permit, even though he speaks fluent Greek…The gangs also hunt the dark-skinned man pushing a shopping cart filled with garbage and scrap metal through the streets. Or the woman with Asian features, who now grabs her child and the paper cup with which she has just been begging in the streets…The Greeks may have come to terms with the fact that the luster of antiquity is long gone. But the notion that Athens, a once-proud city, has now become synonymous with political failure and mismanagement is difficult to take.”

—Julia Amalia Heyer “Amid Debt Crisis, Athens Falls Apart,” Der Spiegel, 28 March, 2012.

3.

“Quod non fecerunt Goti Hoc fecerunt Scoti. [What the Goths left undone has been done by the Scots].”

—Graffiti on the west side of the plundered Athenian Parthenon, source of the so-called “Elgin Marbles,” attributed to George Gordon, Lord Byron, circa 1810.

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the gaslight, candlelight, torch, or starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The citational constellations work to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” They are offered with astonishment and largely without comment. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

Image: Wikipedia Commons

A recent Brain Pickings post on Gertrude Stein’s posthumously published children’s book, To Do: A Book of Alphabets and Birthdays, has sent me on a journey to nonsense. Or rather, it has revived a kind of determination to spread an enthusiasm for reading with your guts and heart, not just your head.

In a press release for her first children’s book, Stein wrote something that could just as easily be applied to her grownup fiction:

Don’t bother about the commas which aren’t there, read the words.

Don’t worry about the sense that is there, read the words faster. If you

have any trouble, read faster and faster until you don’t.

While it’s easier to calibrate your expectations of deliberately nonsensical writing, e.g. Lewis Carroll or Edward Lear, reading for purposes other than understanding gets tricky in other areas. At least, in my mind, readers often resist writing that doesn't immediately make sense, that proceeds with a certain tension-filled ambiguity.

Last week, I came across an htmlgiant post that might be useful in terms of articulating a purpose for reading other than understanding. Before recommending five works of theory (touching upon such topics as "interassemblage haecceities"), Christopher Higgs writes:

I think it’s quite productive to read theory as if it were poetry or fiction,

which is to say as if its primary function was to affect rather than educate...

I read theory and fiction and poetry to experience, to consider, to become

other, to shift, to mutate, to change. I most certainly do not read those things

to understand them.

I was reminded of the first time I encountered Foucault, Derrida, and Lacan in an undergraduate literary theory course (which yes, meant that I was reading in order to understand what was being written). Part of my absolute joy at reading theory was the complete tizzy my head went through in its attempts to grasp or even contain the expanse of the ideas written down. The joy, for me, was the experience of reading it. At times I barely thought my feet were touching ground. In the end, I believe I understood less. And this is wonderful.

My point is not to bash understanding or encourage everyone to smoke pot and listen to whale sounds. I mean, go ahead and all, but what I’d like to promote here is an experience of reading that doesn’t insist on pinning something down. Do not be afraid. Try not to read with the goal of saying “Aha! I get it!” when you’re finished. Allow for uncertainty, for ambiguity, for mystery that resonates beyond the page. Let your senses experience a truth your mind can't get a handle on.

This is also not to encourage laziness; quite the contrary. This is to encourage a kind of pleasure in the sound of words and the power of words to bring you to an unrecognized place.

Don't bother about the commas.

image: guardian.co.uk

Old books! They smell so great! And they’re amazing aide mémoires! My old copy of Ulysses is not so easily coaxed into Wordle manipulation, but it’s got sand from Costa Rican beaches in the splitting glue of its spine, buttery fingerprints on its pages from being read while I ate croissants, and lots of embarrassing underlining, circling, and marginal “insights.”

When you read other people’s old books, you get a similar window into their habits and states of mind. Another example from my shelves: an edition of Beckett’s short prose contained a handwritten note from one stranger to another. I know nothing about them—well, not nothing: one wrote with an exceptional hand and could doodle well. The other was named Tom.

But marginalia’s serendipitous discoveries are made possible only because modern books, codices, are more than merely the information they contain; they are also objects. With eBooks, objecthood becomes problematic. Insofar as they “exist” at all, eBooks are hardly objects. They’re an arrangement of bits on a storage device, hardly dissociable from the device the presents it. And, as we now know, eBooks can be taken from you without someone breaking into your apartment. Notes and highlightings you make on your device aren't really yours to keep, either.

None of this is new anymore. Neither is there much to be done about it, on the broad scale: eReaders and eBooks are here to stay. And the medium is not even a bad one, in and of itself. If we could resolve the privacy issues (when pigs fly), or deal justly with the monetization of your “private” habits (pigs don’t absolutely have to fly for that one, though it is unlikely), some of the data produced could be interesting to future historians studying the tastes of eReader users. Hint: as of today, Kindle-types really liked these sentences, and you can bet that Amazon is keeping records on it all.

But whither the trade in used books as the dominance of the codex withers? The pass-along book trade has never been popular with publishers. It has been seen as a loss of profits, quantified in a way much like the ridiculous amounts estimated to be lost on account of music piracy. (Protip accountant dudes: if consumers don’t have the money, in aggregate, to complete sales “lost” to piracy, those sales weren’t gonna happen in the first place!) So don’t expect a pass-along feature to be built into eBooks any time soon. Which means used bookstores will have to come up with a way to save themselves.

Perhaps they are doomed to employ twee, quirky efforts like Record Store Day. Perhaps we’ll see a Codex Day in the future, when small-run, high-value editions are acquired by ostentatiously self-fashioning consumers.

Perhaps (we might hope) said consumeristas will even leave sticky fingerprints all over their new objects.

Image: flickr user andy54321

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ve been writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 5: South Africa's Riddles

As I read Constance Myburgh’s “Hunter Emmanuel,” [PDF] I was reminded of the literary critic Michael Dirda’s recent Q&A on Reddit:

More than 30 years ago I predicted that mainstream literature would be invaded by "genre" fiction, and this seems to be happening. Writers like Jonathan Lethem, Michael Chabon and others came out of science fiction and comics...I think that we are seeing what SF critic Gary Wolfe calls the "evaporation" of genre lines, and fiction is bursting with all sorts of new inventions and possibilities.

“Hunter Emmanuel” is a hard-boiled detective story torn straight from the headlines of the nineteen-forties. It was published in Jungle Jim, which bills itself as an African pulp fiction magazine. “Hunter Emmanuel” is very much a generic story—not in the figurative sense of being predictable or boring, but in the original and literal sense of adhering to a genre.

Mainstream “literary” fiction itself is a genre of sorts. It is largely realistic, largely psychological, and largely preoccupied with the exacting and poetic use of language. As such, I don’t particularly feel like ranking literary fiction as a genre better or worse than other genres. And that's a good thing, because this story seems to be describing a whole lot more than a detective’s investigation of a disembodied leg in a tree, and the woman the leg came from.

This is a story from South Africa, a country that has experienced splits and divisions of many sorts—political, physical, linguistic, racial. Hunter Emmanuel has decided to figure out how the leg was parted from its owner, why one ended up in a tree and the other ended up in a hospital, and what motives might lurk behind all this. If this story were to be taken as a literary allegory, it wouldn’t be hard to posit that the female represents South Africa in one sense or another, while the male detective is an outsider trying to understand divisive actions already completed. But there isn’t quite enough evidence in this story to complete the analogy. All the same, Jenna Bass, the author and filmmaker who has taken Constance Myburgh as her pseudonym, has expressed openness to such interpretation:

I think many films I’ve made, or written, have political elements, even if not on the same level as The Tunnel; I don’t think you can help it if you live in a country where political decisions are particularly visible. At the same time, I don’t like the idea of profiting off of message-based films.

As with films, so with literature, including the stories in Jungle Jim, which she edits herself. There's clearly much beneath the surface of Myburgh's South African-accented prose, and so I hope the continued adventures of Hunter Emmanuel open doors to more conjectural interpretations.

Here's the story as a PDF: Constance Myburgh's 'Hunter Emmanuel'

Check back for a list of the other bloggers contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: junglejim.org

Looking at Liu Wei’s cityscapes made from old school books, I find myself flooded with a familiar sense of reassurance—of the calm that emanated from the cakey volumes on my parents’ shelves and the delicately preserved archives hidden in libraries. I like these cityscapes in great part because I like old books, and I like seeing things done with them.

Of course, I do have requirements. I wouldn’t want to see old books spliced into wet naps or shredded into lining for a bird cage. Shredded into sentence-sized strips to insulate a special gift, however, I might just get behind.

So. What other ways can we ramp up the nostalgic power and the functionality of our old books?

Aromatherapy. One of the most magical traits of old books is their smell. Part dust, part glue, with a dash of mystery, old books smell like a memory of family dipped in a kind of determined hopefulness. Why not treat old books like potpourri? They've already made the perfume.

Hiding your gun. Faux books have been around for a long time, hiding everything from money to drugs, but don’t you think it’s time to put that revolver in some vintage Chaucer? Or, if you're not the "Just Carry" type, take your precious volumes and chop them into guns. What else are you going to do with that frayed copy of Moby-Dick? Make a gun out of it.

Protection. If you’re not prepared to chisel your old books into guns, they can still be used as weapons. The important part is to keep that stack by your front door to make it easily accessible when you need to clobber somebody. Also, if you don’t want to actually assault someone, you can just give them a stack with overzealous encouragement and expect to never see them again.

Insulation/Wallpaper. Okay. Some of the books in my collection I probably won't ever read again. Once they reach a certain age, I think it’d be a fair and lovely thing to paste them to my walls. True, I have lived in several severe weather climates where I've spent a lot of time blow-drying plastic to my windows. But how wonderful would it be to be surrounded by books, not only with slender spines peeking out from the shelves but entire walls of full covers?

While I'm quite capable of throwing away the most precious and sentimental knick-knacks, there's something about books I have a hard time letting go of. If I can class it up and make some art objects that also act as furniture, I could send fewer boxes off to storage.

image: collabcubed.com

Did you hear? The English language is on its deathbed.

Maybe a peppy blurb is all it needs to bring it back to life.

After all, there's nothing quite like a Hemingway endorsement to make anything legitimate.

Although, David Foster Wallace could probably give him a run for his money in the fanbase department.

But as long as what you're doing can be turned into a catchy song, you're good.

Though, writing such a thing is hardly a walk in the park.

If only everything came with a convenient FAQ, life would be so much easier.

But not even a piece of flash fiction can be summed up that easily.

You're probably just better off scribbling away furiously in your Moleskine.

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ll be writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 4: Zimbabwe's Tongues

Melissa Tandiwe Myambo's "La Salle de Départ" [PDF] straddles the uneasy borders between languages. The title, "Departures Terminal" in French, serves as a warning sign: the story weaves between different tongues, recording its characters' rifts of comprehension.

Because Africa is usually portrayed in the media as a homogeneous continent (or even as one enormous country) and because we monolingual Americans read literature in English, it's easy to overlook the sheer variety of Africa's languages. English is certainly common in many countries there—either as a pidgin, or, because of Britain's colonial impulse, as a full language. But so is French (which boasts another prize as good as the Caine), and Portuguese, and Afrikaans. And then there are the native languages struggling against the European incursors, including Hausa, Wolof, Kinyarwanda, and Arabic.

The story opens with Fatima and her father, an old man who "found it easier to read Arabic than French." (It's not uncommon for Zimbabweans to speak two or more of the country's official languages and a few others.) But what language are the different characters speaking? The story is written entirely in English, and we're given few clues that there is a welter of languages until we're told that Fatima's brother "was unconsciously speaking in English...[before] he suddenly realized what he had done and guiltily resumed in Wolof." This kind of information, about each character's unconscious choice of languages, determines their relationships far more than anything they do to each other.

Language itself is a tool for everybody here. Fatima recalls how "as a child she had thought that eating candy would dulcify her words, make them come out sweet as young coconut milk." And it is a matter of convenience: the child, Ibou, moves to America to learn English, but "learned Spanish faster than English and wrote letters home every week in a mixture of French and Wolof."

But sometimes translation is not enough. Or rather: translation simply does not happen. As the story opens with Fatima failing to understand the little things being said, so it closes with Ibou's uncomprehending stare as Fatima reveals that she is staying behind and watching everybody else come and go. We Westerners might not see it immediately, but there are so many languages in Africa, so many cultures jostling up against each other. And even within a close-knit family—father, uncle, son, mother—those languages and lives can drive them apart by their mere difference.

Here's the story as a PDF: Melissa Tandiwe Myambo's 'La Salle de Départ'

And below is a list of the other bloggers contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: map of languages in Africa, wikimedia.org

Carlos Fuentes, author of two of my favorite novels, The Eagle’s Throne andThe Crystal Frontier, died yesterday. He also wrote a book called Gringo viejo (Old Gringo), which imagines the undocumented end of Ambrose Bierce’s life during the Mexican Revolution. Bierce’s satirical lexicon, The Devil’s Dictionary, was known in its first edition of 1906 as The Cynic’s Word Book. Bierce’s pursuit of truth and political engagement in the Mexican Revolution was decidedly uncynical, however, and his disappearance approaches Quixote-esque proportions of melancholic folly. Fuentes considered Don Quixote the best novel ever written.

1.

“[T]ime will not only tell: Time will sell. One might think that Cervantes was in tune with his times whereas Stendhal consciously wrote for "the happy few" and sold poorly in his own life…Some writers achieve great popularity and then disappear forever. The bestseller lists of the past fifty years are, with a few lively exceptions, a somber graveyard of dead books. Yet permanence is not a willful proposition. No one can write a book aspiring to immortality, for it would then court both ridicule and certain mortality. Plato puts immortality in perspective when he states that eternity, when it moves, becomes time, eternity being a kind of frozen time. And William Blake certainly brings things down to earth: Eternity is in love with the works of time.”

—Carlos Fuentes, “In Praise of the Novel,” 2005.

2.

“DEBT, n. An ingenious substitute for the chain and whip of the slave-driver.

As, pent in an aquarium, the troutlet

Swims round and round his tank to find and outlet,

Pressing his nose against the glass that holds him,

Nor ever sees the prison that enfolds him;

So the poor debtor, seeing naught around him,

Yet feels the narrow limits that impound him,

Grieves at his debt and studies to evade it,

And finds at last he might as well have paid it.”

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary, 1911.

3.

“ ‘Oh!’ responded Sancho, weeping. ‘Don’t die Señor; your grace should take my advice and live for many years, because the greatest madness a man can commit in this life is to let himself die, just like that, without anybody killing him or any other hands ending his life except those of melancholy. Look, don’t be lazy, but get up from that bed and let’s go to the countryside dressed as shepherds, just like we arranged…If you’re dying over sorrow of being defeated, blame me for that, and say you were toppled because I didn’t tighten Rocinante’s cinches…”

— Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote Part II, 1615.

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the gaslight, candlelight, torch, or starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The citational constellations work to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” They are offered with astonishment and largely without comment. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©