“Mother and Daughter” by Egon Schiele (via Wikimedia Commons)

The difficulty of being both mother and author.

Picture a writer at work, cloistered away in a study with a window overlooking a city skyline or perhaps a garden. The cursor’s blinking is interrupted by a flurry of snapping keys like rain hitting a tin roof. The writer pauses to look out the window at nothing in particular, brows knit in contemplation, rummaging for that perfect word.

This idyllic scene is wildly different from what the writer who is also a mother experiences. For her, writing takes place at the dining table amidst the abandoned breakfast dishes. Coffee grows cold, forgotten in the microwave, while cartoon voices blare from the television. The cursor’s blinking is interrupted by the googling of Halloween costumes and dancing cat videos. Words will come, not in meditation but in respite, at the bus stop or in the grocery line, with many to be forgotten soon after they’re found.

Historically, mothers have shouldered the lion’s share of domestic responsibilities. Extracurricular activities, like writing, are just that — extra — to be undertaken only when all other obligations have been met. Consider Anne Bradstreet, an early American poet; her book The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America, published in London in 1650, included a preface explaining that she displayed “exact diligence in her place, and discreet managing of her family occasions” and that her poems were “the fruit of but some few hours, curtailed from her sleep and other refreshments.”

I gagged when first reading this, then happily recalled that I live in the 21st century. Surely that sort of archaic thinking has gone the way of the dinosaurs ... right?

Not really. Though in recent years fathers have stepped up in ways that would have been unheard of even 50 years ago, the truth is that, in popular opinion, parenting is not an equally shared enterprise. Mothers are charged with the majority of the physical and emotional upbringing of their children — and in the case of single mothers, the totality of it. Mothers are the ones made to feel shame over a son’s unwashed face or a daughter’s unkempt hair, and mothers are responsible for the little things — school lunches, matched socks, on-time bedtime. It’s often those little things that crowd the creative mind, leaving little room to stretch.

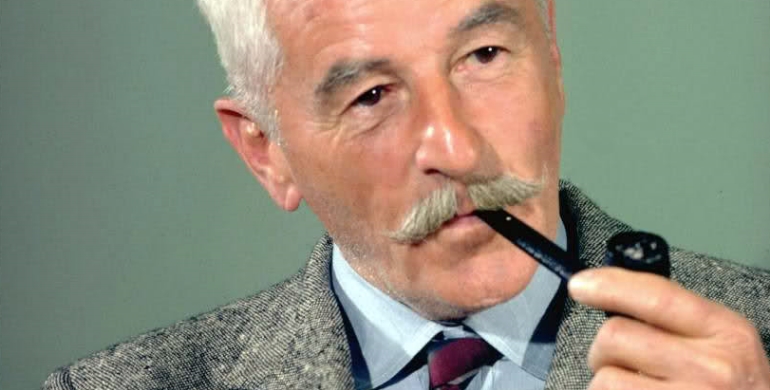

Lorrie Moore (via IFOA)

In a 2001 interview with The Paris Review, Lorrie Moore, who writes with savage honesty and stunning beauty, articulated the difficult position women find themselves in when attempting to be both mother and author:

The ability to make a literary life while teaching and parenting (to say nothing of housework) is sometimes beyond me. I don’t feel completely outwitted by it but it is increasingly a struggle. … It’s hardly news that it is difficult to keep the intellectual and artistic hum of your brain going when one is mired in housewifery.

Moore’s most recent book, Bark, a collection of short stories, has received mixed reviews. Joyce Carol Oates praised it in The New York Review of Books, calling it “mordantly funny and heartbreaking,” while Michiko Kakutani gave it a scathing review in The New York Times. Mainly Bark has been criticized for its length. It is slim in comparison to Moore’s other collections like Self-Help and Birds of America, containing only eight stories, but I surmise that its slimness isn’t evidence of negligence or laziness; it’s evidence of a full life, evidence of her determination, of her belligerent insistence on writing, on keeping her creative mind alive while juggling all of life’s flaming sticks — including being a single mother.

In addition to working and cleaning and cooking and laundering and living and writing and publishing, Moore gave birth and raised to adulthood another human being. Perhaps we should keep that in mind when considering the length of her ninth book.

Trisha Leon is a freelance writer and student of English at Cedar Crest College in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©