I walked through the pouring rain to the opening night of Chris Ware's gallery exhibition. His latest book, Building Stories, just came out, and I wanted to see the artistic process behind my favorite book cover and, well,

I wanted to see who else was obsessed with this graphic-novel master.

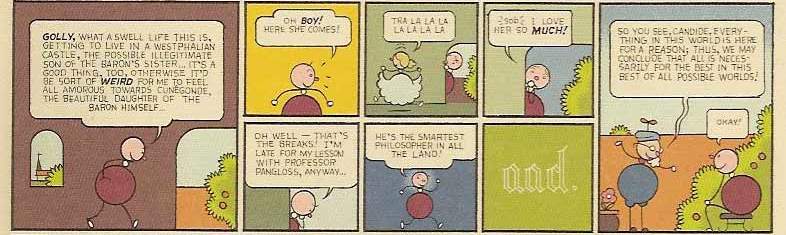

There were a few people who, like me, were sipping white wine and looking at the panels for the sheer enjoyment of it all. I first learned about Chris Ware when I held Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth in my hands. Not knowing what to expect, I had flipped through the book and seen a wide array of ligne-claire faces (just like Hergé's Tintin series!) and carefully proportioned panels that were way more complicated than the Batman comics I'd read in grade school. And this Jimmy Corrigan wasn't a little kid, either. He was a middle-aged man and his entire life was depicted in hundreds of pages, some without any text at all (including some beautiful montages of the sun moving across landscapes), and some swallowed up by a single panel. I was hooked.

I read this book when I was seventeen, so I wasn't terribly surprised to see a few high-school students with backpacks peering at the art gallery's walls. They looked, snapped pictures, and then texted their friends.

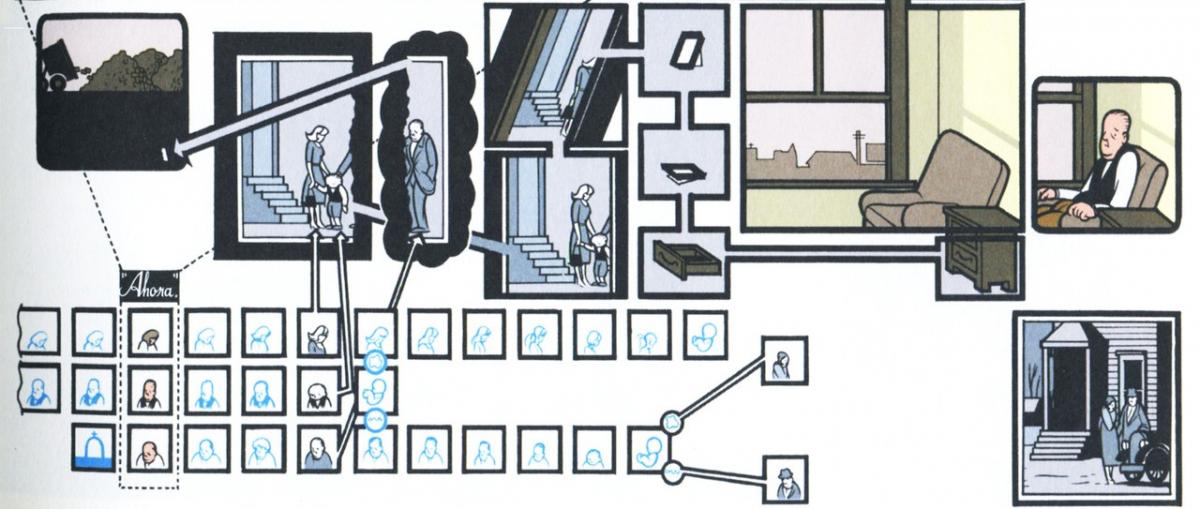

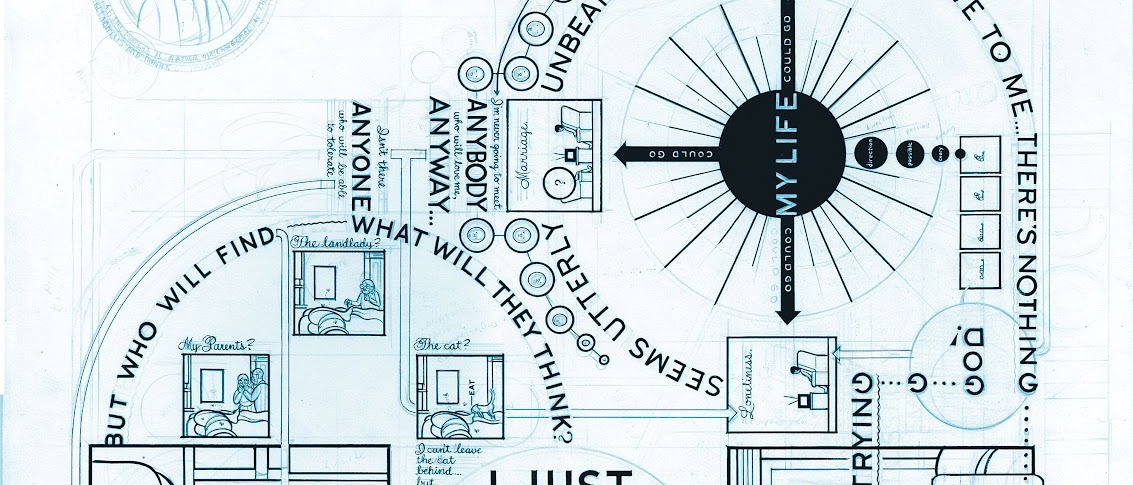

The title of Chris Ware's Building Stories is a double entendre, of course: even as he details the lives of various inhabitants within a single apartment building, he lays bare the ways in which he constructed those stories. I love sketches and other evidence of the artistic process, and so I wasn't disappointed to see

gigantic pages that swirled with text and images laid out in all directions. Even in the most chaotic pages, Chris Ware so clearly anticipated the human eye's motions that I was able to piece together the stories he was telling. And it wasn't just the eye that he understood; as I read the stories of men and women, children and adults, I realized that he had found a way to encapsulate the difficulty and beauty of human life into squares and lines.

Near the end of one panel, a mother tells her grown daughter that she dreamed she had found a book filled with everything she'd done in her life: "The point is, I dreamed [it up]... I saw it — made it — with my own two eyes [...] I just never thought I had it in me, that's all, you know? *snf* ... I never thought I actually had it in me..." I'm pretty sure Chris Ware himself walked past me at that moment, or at least I hope he did. He reportedly struggled over the years of Building Stories's creation; he mentions the almost complete loss of his virility, and he's notoriously press-shy. This was the first time I had seen that particular strain of grief, recognition, and summation immortalized in art.

I repeatedly squeezed past a man who was holding a baby. Another type of person I hadn't expected to see at a gallery opening. Maybe these comics looked kid-friendly on the outside? Or they were just looking at the model house built by the artist? Ware's characters are so driven by feelings of longing, guilt, despair, surprise, and sexuality that I almost worry about minors looking at them.

But out of Ware's honesty great beauty arises: sequential art that can modulate the passage of time and memory, that can move us (in one of my favorite panels, linked above) from a drop of water falling to a woman checking the time and, in her mind, seeing daisies. I knew I had to buy the entire Building Stories and open the box with its fourteen different booklets and posters and newspapers inside. I kept looking at the panels along the wall. I forgot all the unexpected people around me and lost myself in Chris Ware's square panels, solid colors, and clear lines.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©