I’m writing this at the library. The Mechanic’s Institute Library is the oldest library on the West Coast. The crowning feature of its 1909 building is an iron-and-marble spiral staircase that looks like a nautilus shell when viewed from upper floors. I’m sitting in the third-floor reading room looking out at the Crocker Galleria, an odd glass-canopied indoor/outdoor mall in the middle of the otherwise urban landscape of the financial district. If the Mechanics Institute is a distinguished old gentleman, the Galleria is standing across the street rolling its eyes like a 1980s teenager. There’s a huge clock in the façade of the Galleria, and when I look at it, I realize I should be getting back to my work.

In the silence of the library, the muted clack of old men shuffling wooden newspaper dowels is about equal in volume to the blur of traffic three floors down. But the loudest thing I can hear is a steady tick, tick, tick that I can’t source. I look out the window, at the giant mall clock: It has no second hand. I close my eyes and focus on the sound, the ticking, that penetrating sound that can keep me up at night, the reason I have no clocks in my bedroom. Tick, tick, tick. It’s coming from nearby, from inside the library. I realize it’s coming from my watch.

My rotary watch was a gift to myself when I first purchased a smartphone a year ago. I hoped wearing a watch would remind me not to rely on my phone for every single piece of information in my life. My new, antiquated watch has a gold-hued face that reminds me of a classic train-station clock, the kind from old films I used to obsessively watch as a teenager; its overly wide watchband surrounds my wrist in soft, imperfect leather that reminds me I used to be sort of punk rock. I’ve never before noticed the sound this watch emits, but I’m not surprised when I find myself wishing the librarian would shush it for me. It hurts my brain.

It's a natural reaction; I’ve just come from looking at the most mentally penetrating clock I’ve ever seen: Christan Marclay’s 2010 film installation “The Clock.” I sat inside “The Clock” for as many hours as I could, and then I left it and walked out into the city and went to the library to write about it. Everything still ticks.

In a film scene from my memory, two men in dark suits — William Holden and Karl Malden, perhaps — stand in front of an abnormally large modern clock mounted on wallpaper thick with ornate flowers. In front of them, a woman in a stiff, short A-line dress sobs, then falls into the arms of a cop standing nearby. Even further in the foreground, skewing the viewer’s perception of depth, a big white bald man stands in silhouette. It’s 9:30 P.M., according to “The Clock.”

"I saw about 20 hours of 'The Clock' over the course of two months and six visits."

“The Clock” brought artist Christian Marclay’s predilection for remixing popular cultural objects into artistic statements to its largest scale yet. “The Clock” is a 24-hour film composed of brief clips of other films in which clocks or times are shown or mentioned. Every moment onscreen occurs in local time, so when it’s noon inside “The Clock,” it’s also noon outside, in real life. For example, at 5 P.M., the exhibition’s perpetual montage consists mainly of clips of people leaving work, often by train, as whistles and clock chimes mingle in a rush hour cacophony. At the same time, just beyond the doors of the gallery or the museum, real-world commuters are heading home.

Marclay enlisted a computer scientist to build a custom program that links the 24-hour loop of video and audio precisely with real time, effectively making “The Clock” into a clock itself. As such, the installation is an interesting intersection of several time-based experiences: It’s a clock made out of films, a history of film (which is also, coincidentally, a history of the last century) and an investigation into the physical experience of time and memory.

This spring, “The Clock” was shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in a small theater. Because it’s a clock, “The Clock” played constantly, even when the museum was closed; but for several weekends, the institution stayed open all weekend to afford visitors a chance to watch the less waking hours tick by.

To see “The Clock” at SFMOMA, audience members are ushered into a dark theater by flashlight-bearing attendants. Viewers are assigned a place to sit one by one (which means you probably can’t sit with your party). The theater seats about 80 people, who sit in groups of three in artist-mandated, light-grey IKEA couches arranged in careful rows. The museum attendants I spoke with on opening weekend said that Marclay had supervised the installation himself; he’s reportedly particular about the in-theater experience and especially adamant about people being allowed to stay inside “The Clock” as long as they want. Accordingly, it often takes hours to gain entry, and the warped sense of time spent waiting in line adds to the temporal distortion of the exhibit.

The entire experience is, by most accounts, a trippy one. The film itself is riveting. By nature, most of the moments in movies that feature clocks or discuss time are ones of pressure or climax. Marclay’s pasted-together scenes may portray farcical capers, romantic declarations, literal and figurative blowups or tense waiting games, but they always revolve around a heightened sense of anticipation. Something is always about to happen.

I saw about 20 hours of “The Clock” over the course of two months and six visits. Whenever I was in the theater, I always caught myself checking my watch, even though I knew the film I was watching only had one line of inquiry: What time is it? Still, I repeatedly felt compelled to check my watch. I was anxious. How long was I going to stay? What if I missed a good part? How long has it been? What time is it?

“The Clock” invites big questions: How do we as humans invent and mark time? How does this act shape us and structure our lives? What do movies have to do with memory? What was the name of that one movie with Karl Malden and William Holden? (It’s Wild Rovers, according to Google, and from the looks of it, it’s a Western and would have nothing to do with the visual impression I have of a sobbing woman and a cop and a spooky wall clock. That’s what hours of montage at a time can do to the brain: meld one film, era, genre atop another.)

“The Clock” can, of course, be tiring if one decides to stay for many hours, but the main physical effects of the film are felt after emerging: Sometimes it’s night; sometimes it’s day; always, my eyes hurt.

The night I couldn’t escape the image of the sobbing woman from a film I’ll probably never locate, I left the theater at 2 A.M. Because of the hours I’d just spent watching a bright screen in a dark room and the sleep I’d missed doing so, my naturally weak eye muscles had trouble focusing. I saw double as I struggled through Yerba Buena Gardens looking for my locked bike. Everywhere I turned, time made its presence known to me.

The moon passed overhead in its nightly rotation. Clouds moved over it as though in fast-motion. Clocks chimed out from an old brick church over whose roofline the modern blue cube of another building peeked like a rising, angular planet. Forget what time it was, what year was it?

I found my bike and wheeled down Market Street, missing the bustle and cross-traffic of daytime in San Francisco’s financial district. I rode towards the water and the Bay Bridge’s feet. Ahead of me, the street’s slight downward slope bottomed out at a towering clock atop the Ferry Building. I aimed for that clock, focusing, and it waited for me, static, like a target or a parent watching my late-night stumble into its reach. The blue of the sky and the yellows of the streetlights flickering by me left an imprint in my sight like a changeover cue.

“The Clock” compounds movies with time, which are both made up of what can essentially be called scenes. Time makes sense. Human life is full of experiences that seem to lack order or sequence; because we are humans, we then seek to divide our lives into segments in a way that helps us maintain some sense of collective narrative order. So we use time to break experience into distinct units, often based in our observations of nature: This was in the Fall of That Year. We also make instruments to keep track of those units. We put these instruments in every room of our homes, on city streets and atop public edifices, inside our artistic and cultural renderings, even on and beside our bodies. Relationships with clocks are constant and intimate, public and private. But until I saw “The Clock,” I barely noticed.

On one of my last trips to see the piece, at 10:20 A.M., I stood in line with my childhood best friend while her young children were at school. My friend and I have both worked extensively in the nonprofit arts; we’d recently been complaining to one another that it had been years since either of us saw a piece or performance that genuinely moved us. I brought her to “The Clock” hoping she’d share my excitement about its ability to alter a viewer’s perception of physical time and tap into the memorial power of cinema.

While we were waiting in line for an hour and a half, we caught up, talked about the arts in San Francisco and the impending renovation of the museum we were standing in. We talked about time-based art, resurrecting our best theory-speak from earlier eras. At one point, she asked me if I still had the Moon Clock.

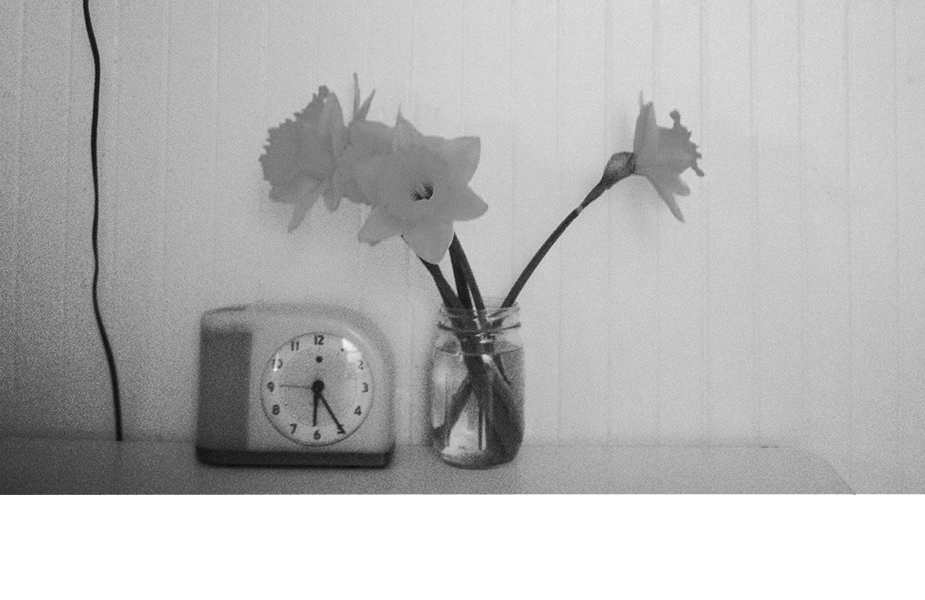

Early in their courtship, my friend’s husband bought a clock we all took to calling the Moon Clock. It’s a small clock, likely from the 1950s, constructed of a warm, aged yellow plastic in a half-moon curve on top and a flat bottom, all of which lights up. The Moon Clock had been my friend’s bedroom clock for years; after her first child was born, it served as a nightlight until the picky tastes of toddlerhood banished it to a closet. She offered it to me.

"Its time might be over."

Because of its analog hum and its association with my closest friends’ private space, the Moon Clock felt like home to me, like history. I placed it on my kitchen table and kept cut flowers next to it — a lily from a boy I love, an iris to welcome spring, a bouquet of dried fall fare to last through the winter. While sweeping my kitchen one morning, I moved the kitchen table and the clock was jostled a bit. It stopped.

Near my apartment in San Francisco, there is one remaining clock repair shop: Klotz Watches, a small storefront in the Castro neighborhood run by two surly men who speak in unplaceable but definitely Northern European accents. They keep odd hours.

I walked to the shop with the surprisingly heavy Moon Clock in a paper shopping bag. I placed it on the counter, and Klotz (who may or may not actually be named Klotz) grunted at me:

“Those, they don’t come back.”

“You mean you can’t fix it?” I’d barely set the thing down on the counter yet.

“Ja, I can fix it, but the parts, they are hard to find. Expensive if you find it.”

“Can you just open it up to see what’s wrong?” I said. “I mean, it might just need to be tightened or something?”

“These are electric clocks. Westclox.”

“I know it’s electric, but doesn’t it still have, you know ... parts? That might be repaired or replaced?”

He smiled, somehow still unsympathetic. “That part, it costs like three, four-hundred dollars,” he explained as though to a small child. “If you can find it.”

“Well, can you at least just look at it and give me an estimate?”

He handed me a yellow paper slip, the likes of which you don’t see at small businesses much these days, stamped with “KLOTZ WATCHES” across the top. I filled in my name and phone number. He taped it to the Moon Clock and took it into the back room. Through the doorway, I could see a mess of shelves, spiral springs, parts and a tiny soldering rig hooked up to what looked like a magnifying glasses.

I never saw the Moon Clock again.

Sometimes I call the shop back to ask about the Moon Clock, and no one answers the phone. I leave messages, short ones and long ones, apologizing or being outraged, but no one calls back. I return to Klotz periodically, walking 20 minutes from my apartment to the shop, but Klotz’s erratic schedule never syncs with mine.

I picture the Moon Clock on a back shelf behind the soldering table, waiting for its part I can’t afford. I could try harder to get it. I could save up money to fix it. I could go in now, more than eight months after I left the Moon Clock there, and stare down Klotz’s cold northern smile. But he might still be right: Its time might be over.

At the museum, waiting in line, I told my friend about the Moon Clock, afraid she’d be upset. “Oh, bummer,” she said. “Yeah, it was old.”

Clocks are everywhere, and they blend: on buildings, in churches, scrolling across digital displays on bus stops.

In 2003, I had recently moved back to San Francisco after stints in several other states. I found a job writing marketing copy for an arts organization downtown. On my first day, nervous and overdressed, I disembarked from my bus on Market Street and got turned around trying to find my new office. I found myself instead standing beneath a towering gold pillar on the sidewalk, looking up at the clock on top of it, trying to find my bearings.

"It always says 9:02, 12:31, 5:07 or whatever time is inconvenient for me."

The Samuels Clock was erected by Albert Samuels in 1915 outside his clock shop on Market Street, which later moved to its current location, in front of 856 Market. The clock itself is golden and rotund, and better read from a distance due to its height. At the base of the clock is its most unusual feature: another smaller clock — actually four clocks, one each side of the square midsection — and below that, a box-like column that’s walled on all four sides with glass. Visible through the glass, the machinery within whirs, a perpetual algorithmic dance of chains and wheels and gears.

On the way to my new job 10 years ago, I had stared only upward, searching for the Samuels Clock’s face. I didn’t even noticing its intricate open-faced innards because I was late. I was always late to that job; in four years, I was never not late. Every morning, I passed that clock. I still pass it now, on my way to the Mechanics Library. It always says 9:02, 12:31, 5:07 or whatever time is inconvenient for me.

During the months I was watching “The Clock,” I happened to visit New York, where I lived in my early twenties. It was spring, one of those weeks when the city lives up to its legend in the best of ways. The buildings seemed taller, the crowds more purposeful, the sidewalks cleaner, the people louder. Everything shimmered with sophistication and toughness and promise.

One morning, I walked through Central Park in showers of cherry blossoms with a quiet friend. Near the boat house, the sound of a large orchestral ensemble playing a haunting chorus drew us towards a space beneath a bridge overpass. When we approached, however, it was only four people. The violin soloist yawned, sleepy like a boy in his nursery echo chamber. Crowds of tourists were there, too, and they took photos. “It’s like a movie,” someone said.

After my friend left, I kept walking, across the park and into midtown, all the way down 2nd Avenue, and I ended up near my old apartment on the Lower East Side.

I moved to New York at 19 years old in a brown Subaru station wagon my best friend and I drove there from California. We hung hand-sewn curtains in the car’s windows and drew them tight while we slept in rest stops, in tree-lined neighborhoods, on the side of the road for six weeks across the country.

Somewhere on that trip, I lost the cheap Casio watch I always wore. On the road, however, I didn’t need to know what time it was, not really, and once I hit the ground in New York, there were clocks everywhere. Anywhere in Manhattan, wherever I lived, I could look up or across the street or into the sky and learn what time it was. Where there wasn’t a clock on an ancient-looking stone or new steel façade, there were people. People wore watches or carried beepers (yeah, it was 1996), and these people were always willing to answer a stranger when she hurled, “You got the time?” at them on the train or in a bodega.

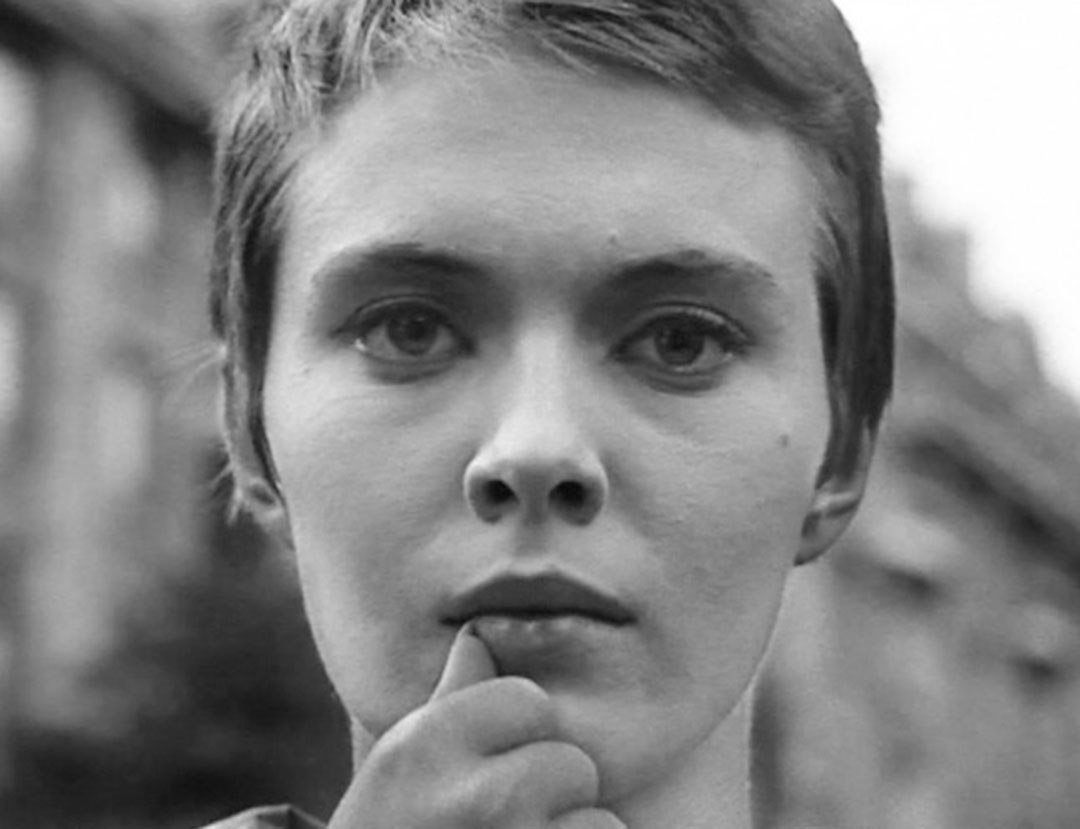

I carried with me to New York a postcard of a Cindy Sherman photograph my mom had once given me. The photo, from Sherman’s “film stills” series, depicts a young woman dressed in a 1960s-style collared shirt and short hair, a small hat titled back on her head. The girl is foregrounded in front of the crisp architecture of two skyscrapers, and she’s delivering a slightly disbelieving squint just past the camera. She is all urban and attitude, and I wanted to become her. I towed that postcard in my notebook across the country and up and down Manhattan for at least a year before I read the back and realized it wasn’t from an actual movie.

I pasted the Cindy Sherman postcard on the wall of my apartment, a one-bedroom on the Lower East Side that I shared with an artist friend. From my bedroom window, I had a view of the bar across the street, the blinking glow of the 24-hour falafel place just above the bar’s roofline and, about a block east, a large red apartment complex known as Red Square.

Atop Red Square’s highest tower was a tremendous clock, its face entirely visible from my bed. I called it the Lenin clock because in front of it stood a sculpture: Vladimir Lenin, hand upraised in what I imagined was a perpetual challenge to the ruling, uptown classes of Manhattan. The clock itself, called “Askew,” was made by Tibor Kalman. Its numbers are misplaced — a six where the three should be, a two where the nine goes, etc. — in a pattern or method I’ve never figured out, but the clock’s hands keep proper time. In the four years I lived in that apartment, the Lenin clock became my only watch, its irregularities blurring into order as I woke, left for work, came home and watched the light fall to the pace of its hands.

On my recent visit, I hesitated to go back to my old block on Orchard Street. The neighborhood was quiet that afternoon, though it never used to be. The street has seen endless change since (and before) my time there, but this visit felt different. The chic demeanor of the most recent wave of boutiques and upscale bars had turned ragged: traces of bleariness had edged into the neighborhood’s new tempered steel and glass edifices. An entire section of the block across the street from my building was gone, demolished to make way for another building that would likely see the same fate. I felt as though the layers of economic exploitation and class striving common to the neighborhood in all its incarnations had finally been cycled through enough times to be worn thin, like tractor treads or reels of film seconds before catching fire.

As dusk came on, I stood against the brick wall outside my old doorway and watched the lights of Manhattan wake up. I looked up at Lenin, fist still upraised, and he was smaller than I recalled him appearing from my bedroom window. I bought a postcard of my block at the Tenement Museum and made sure to read the back, made sure it was real.

Although my cheap Casio watch never lived in New York, it was well traveled. Before I lost it on the road, the watch went with me to Paris. In Paris, I didn’t use it much; I may even have stashed it away in my luggage once I realized the existence of the church bells of Europe. To a 19-year-old American, the church bells of Europe are everywhere, harsh, harmonious, incessant, a marvel. They go off at indeterminable times of day. They clash and sync like movements across the span of centuries.

I was alone in Paris. I hadn’t intended to be; I went there to meet a boy. This boy was nice and smart, but he lived in a city thousands of miles across the country from me. Instead of the usual young adult courtship rituals, we exchanged endless rounds of long-distance phone calls and mix-tapes. We bonded over our shared love of 1960s jazz and film, specifically French New Wave. We admired the style of the young lovers in the Jean Luc Godard film Breathless, if not their unhappy ending; I cut my hair short like Jean Seberg. It was ridiculous and romantic. At some point, the boy said he was going to Paris with a 16mm film camera. So I gave notice on my first San Francisco apartment, bought an open-ended plane ticket and said yes.

He left me, and quickly. I was heartbroken — but I was in Paris. I took my one bag of luggage and found a place to stay through an old acquaintance of my mom. I decided I’d just have to reorient, and set out to make myself into Seberg after the movie ends — or perhaps someone even stronger, like a girl saint.

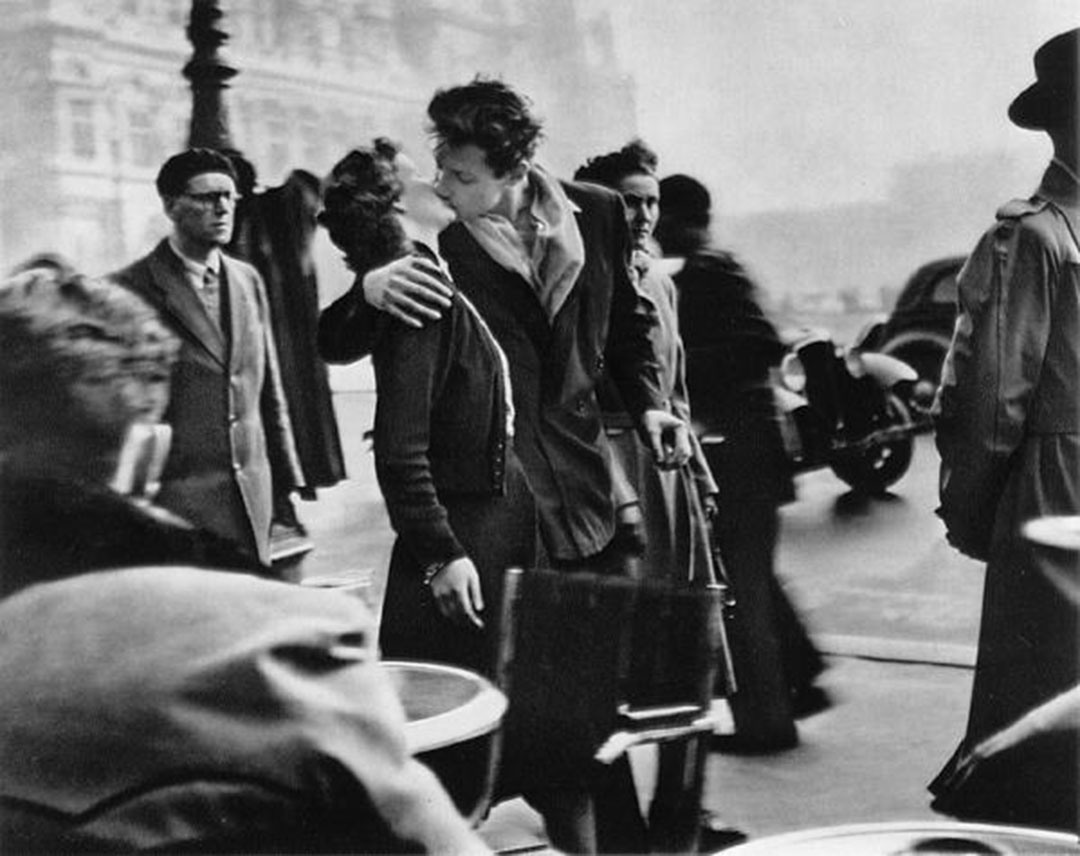

At the same time, there was a public service sector strike. That meant no trains. No subways or buses. Taxis were a luxury for the well connected. So I started walking. I walked every day, all day, through the iconic daily existence of Paris: Past shady bars near Bastille; through the plaza outside the Hotel de Ville where Robert Doisneau staged his famous photo of that couple kissing; in front of Shakespeare & Co., where I asked a strange man for a light in French and he replied, “I don’t speak French” in a New York accent. I walked around the Sorbonne, where protesting kids once broke the windows of the McDonald’s with only the public toilet in the area; I walked past the Turkish guys at the café where I wrote and by the newsstand owned by the two Algerian men who called me “California.” The streets were steamy, people hurried, the beep-beep of European sirens blared and blended with the resolutions of chords sung by the church bells always above us. Snow formed and failed, and tried again to form.

Most mornings, I left my place in the 19th arrondissement and first trekked about an hour across town, over the Seine and into the Left Bank, as though I could resurrect the intended romance of my trip to Paris by haunting its most clichéd quarter. My route took me past the cathedral of Notre Dame, whose wooden-geared clock presides like an afterthought over its dense faces.

I never read the classic novel about the clock tower of Notre Dame or even saw the Disney movie, but the clock held power for me. Beneath it, inside the cathedral, were horrors and histories that held the type of stories I had come to Paris to find. They made my grief over a false start of a relationship feel small. The cathedral was free to enter, and warmer than the street. I made it a daily stopping point.

"She had run out of time in her life, and I, I hoped, was just beginning mine."

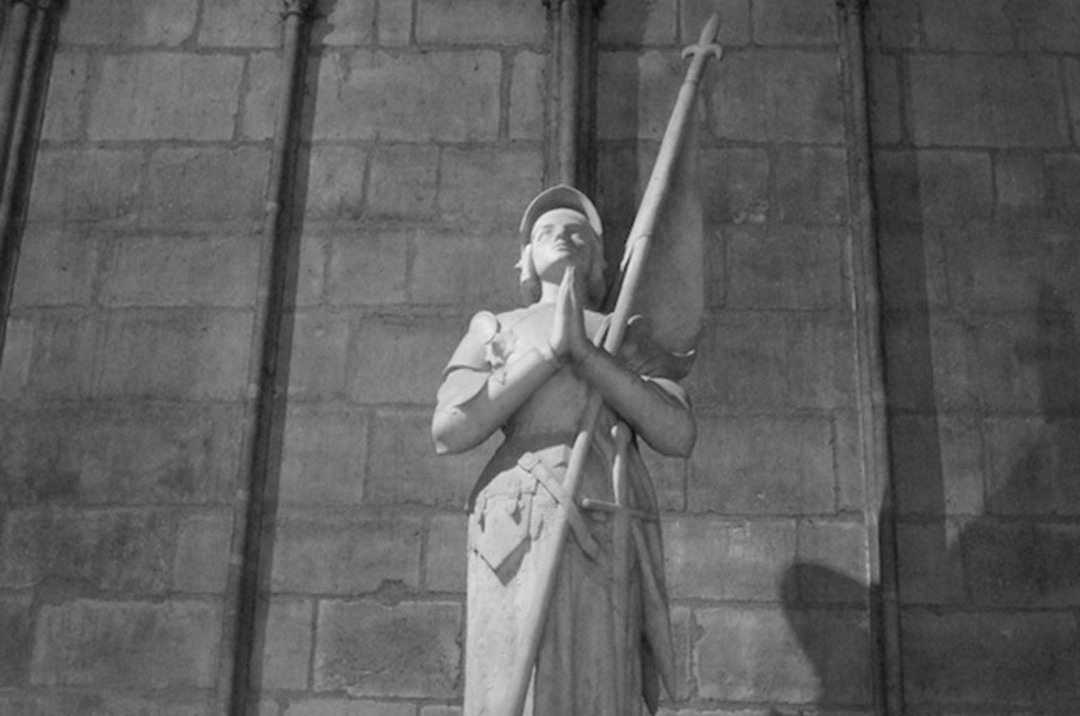

When the tower bells rang, they rolled like marbles through the church’s smallest stone corners. In one of those corners, tucked away in an unassuming chapel near an emergency exit door, I discovered a sculpture of Joan of Arc. She was beatified in Notre Dame in 1909, and she’s now represented within its embrace in simple, clean stone, staring upwards as though she were searching out the source of the music that fills the windows above her as worshippers fill the pews.

I never prayed in Notre Dame, but I did whisper to Joan when I felt sad and cold. She was about my age, I reasoned. She had run out of time in her life, and I, I hoped, was just beginning mine.

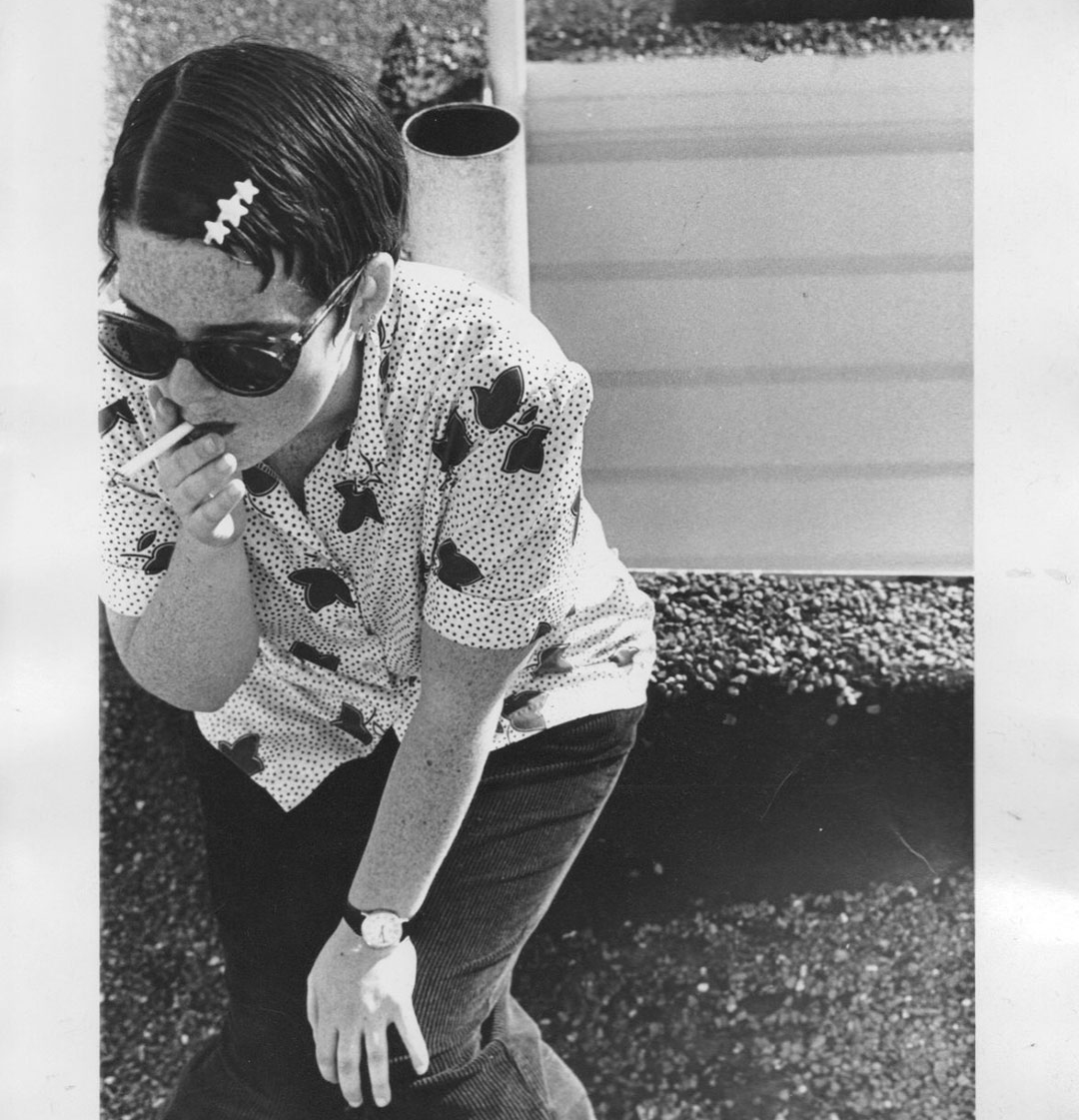

There’s an old photo of me sitting on a rooftop in San Francisco shortly before I left for Paris. In the photo, my hair is cropped short like Jean Seberg’s, and I’m wearing the lost Casio watch, the last watch I owned before my current, smartphone-inspired timepiece. It was a $15 watch with a big clean white face and numbers in a tasteful but generic typeface. I bought it in a Longs drugstore. In the photo (a pre-digital, wrinkled, 8 ½ by 11 inch print), I look too cool to exist. At least that’s what I think now, almost 20 years later, when I look at that girl in that pixie cut and those Adidas and that unfiltered cigarette dangling from her hand. My artist roommate, who would later become my roommate in New York, took the picture, and it’s well taken. The gravel of the tar rooftop plays off the patterns of my freckles, a contrast of light and texture that could only exist on film.

In 1995, I was wrapping up my first year in San Francisco. I was 18. I felt an ownership of San Francisco from the start. I liked how it was loose and loud, dirty and pretty, without the pressures of the ambition that I would later recognize as a hallmark of New York. My friends and I were poor but resourceful. We felt like we had the run of all the rooftops, illegal-entry bars and bus backseats we could handle between our service job shifts and our frenetic creative projects.

That same year, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opened a brand new building. Designed by Mario Botta, it was architecturally scandalous, as all large-scale public architectural projects are. It was the biggest museum in the West, and it was ours.

The Botta SFMOMA building is a space filled with natural light, more so than any other museum I’ve been in. It’s crowned by a large white circular skylight, which lends the museum the air of a cathedral despite its otherwise boxy shape. The museum is small and feels so, but its size also makes it feel comfortable, almost homey.

I hadn’t grown up in a large city, so SFMOMA was the first museum I ever visited, ever knew. When the building opened, my friends and I went, along with the rest of the city. We paused on its black-marbled stairwell and climbed the stairs to its pristine white footbridge. I don’t remember how we paid for it or what it cost, but I remember the newness of feeling that a place was within my reach, that I could become acquainted with art.

That year, Mario Botta said of his building, "The architect works in the territory of memory." As I’ve visited this building over almost two decades, it has become a territory of memories for me, too: sensations and recollections of the space itself, and also of the century’s worth of scenes catalogued within its walls. To me, the building has been a container whose contents changed but were always familiar, a starting point whose exhibits I could use to mark eras in my lifetime.

In June, the Botta building closed forever in its current form. Only 18 years after its creation, it had became too small to display the museum’s collection. SFMOMA will be closed for three years, during which time an epic addition/renovation will take place. Designed by architecture firm Snohetta, the plans for the new building promise to leave intact most of the preexisting building’s most iconic features (and its boxiness) by adding an an awkwardly rendered, L-shaped white extension behind the current building.

The museum held special weekend-long parties the entire month of May before sending its visitors off and hoping we return in three years. Appropriate for a celebration honoring the end of one era and marking the anticipation of another, the final exhibition shown in the old building was “The Clock.”

Manjula Martin lives and writes in San Francisco. Twitter / Tumblr / Scratch