On March 9, 1913 — 101 years ago yesterday — Virginia Woolf delivered her first novel, The Voyage Out, to her first publisher, Duckworth. Throughout her career, Woolf was the master of revealing characters’ most intimate judgements, longings and insecurities through stream-of-conscious narratives. She gave readers access to all of her characters’ thoughts whether they were reflecting, looking at others from a distance, coming together for dinner parties or running into people on the street. You cannot read Woolf without knowing just how everything affects each of her characters.

In Woolf’s classic essay Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown, she responds to an article by English writer Arnold Bennett, in which he argued that early 20th century authors were failing to write great novels because they failed to create tangible characters: “The foundation of good fiction is character-creating and nothing else.” Woolf weighs Bennett’s literary theories and speculations against her own experience and argues that every person, anyone who’s lived, is a natural judge of character, but that a true skill for character-reading (Woolf’s term for people-watching for the sake of constructing fictional characters) requires practice. Woolf illustrates how she goes about character-reading by recalling a woman she became fascinated with while riding the train from Richmond to Waterloo. This “Mrs. Brown” gives readers a glimpse into Woolf’s process of writing and, more specifically, creating characters. In the essay, Woolf argues, “I believe that all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite.”

Woolf’s essay is somewhat dated. These days, literary writers aren’t divided in two camps, being Edwardians and Georgians, but there still are so many great points to take from Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown. These are 10 solid rules from Woolf’s famous essay:

1. Practice character-reading until you can “live a single year of life without disaster.”

This is perhaps the most gutsy advice Woolf offers. So many writers will advise you to live wildly, to fail, to suffer and bleed for your art — anything for a great life story that will give you the inspiration to write from. But Woolf makes a great point: finding inspiration doesn’t always have to be so hard on writers. It can be done simply, day by day, in trying to understand the people around you and having the courage to have a little empathy.

2. Observe strangers. Let your own version of their life story shoot through your head — how they got where they are now, where they might be going — and fill in the blanks for yourself.

When Woolf describes taking a seat across from Mrs. Brown, she describes her attire, her tidiness and her facial expression, but Woolf also lets her mind wander beyond what she sees. She lets traits serve as clues to what could be fictionalized:

There was something pinched about her — a look of suffering, of apprehension, and, in addition, she was extremely small. Her feet, in their clean little boots, scarcely touched the floor. I felt she had nobody to support her; that she had made up her mind for herself; that, having been deserted, or left a widow, years ago, she had led an anxious, harried life, bringing up an only son, perhaps, who as likely as not, was by this time beginning to go to the bad.

3. Eavesdrop. Listen to the way people speak, but pay special attention to their silence.

Eavesdropping is the oldest trick in the book in terms of learning to craft believable dialogue, but it can be just as helpful in understanding how to create generally believable characters. Of course, Woolf doesn’t dismiss silence, especially as far as conversations are involved. Silence can lead to uneasiness, as it does in Mrs. Brown’s conversation, and be revealing not only about a relationship, but each individual’s ability — or inability — to deal with uncertainty. Do they fidget? Do they quiet their voice or try to make it brighter to stir up conversation again? Do they do as Mrs. Brown finds herself doing to break the silence with non-sequiturs? One should be so lucky to get a non-sequitur like Mrs. Brown’s: “Can you tell me if an oak-tree dies when the leaves have been eaten for two years in succession by caterpillars?”

4. Write characters who are both “very small and very tenacious; at once very frail and very heroic.” Let them have contradictions.

As Woolf watches Mrs. Brown exit the train, she makes clear exactly what fascinates her about the woman: Mrs. Brown is full of contradictions. Initially, Mrs. Brown caught Woolf’s eye because of a tense conversation Woolf overheard between her and a younger man, but Woolf focuses most of her attention on Mrs. Brown, who speaks “quite brightly” and then begins to cry suddenly when the man tells her about his fruit farm in Kent. Woolf calls it a “very odd thing” to see Mrs. Brown respond by dabbing her eyes, but it leaves room for the author to imagine the story for herself.

5. Write about people who make an overwhelming impression on you. Let yourself be obsessed.

“Here is a character imposing itself on another person. Here is Mrs. Brown making someone begin almost automatically to write a novel about her.” Woolf makes the point that sometimes you don’t even need to seek out interesting people to observe — sometimes your characters find you. There’s no telling who will captivate you or any explanation of the serendipity of crossing paths, but when you do, write it all down. Let yourself be that crazed person.

6. A believable character is never just a list of traits or biographical facts.

Imagine the most dry way possible in getting to know someone: “What’s your name? Occupation? Where are you from?” Sure, these things are informative, but Woolf argues that good characters aren’t conveyed by merely rattling off a few facts. This, of course, goes back to the limitations Woolf stresses about the Edwardian style of the time and argues to avoid constructing characters by simply researching what the character’s father did for a living, or ascertaining their cost of rent, or figuring out what year their mother died. Of course, some writers like to start with biographical facts and fictionalize from there, but it’s clear that, for Woolf, knowing those things dulled her sense of creativity and openness to imagine whatever she wanted of them. Either way, Woolf got it right when she argued that just thinking of someone as a list of physical traits or a pawn on a timeline isn’t enough to create a convincing character.

7. Illustrate your characters outside of the superficial standards of their time. Let them be complex.

Woolf admits that writing for other people — for a public — can be intimidating. Will they hate my character? Will they find them unbelievable? At one point, she even makes a remark about the British public sitting by the writer saying: “Old women have houses. They have fathers. They have incomes. They have servants. They have water bottles. That is how we know that they are old women.” But Woolf argues that if you write a fictional character with conviction, if you can convince the public of anything, even that “All woman have tails, and all men humps.”

8. Any captivating protagonist should be someone you can imagine in “the center of all sorts of scenes.”

Part of what Mrs. Brown’s “overwhelming and peculiar impression” does to Woolf is inspire her to try to fill in the mystery of her character. She starts to imagine Mrs. Brown outside the incident, “in a seaside house, among queer ornaments: sea-urchins, models of ships in glass cases. Her husband’s medals on the mantlepiece.” But Woolf can also imagine scenes of Mrs. Brown alone, the young man from the train “blowing in” to her secluded home. She could see her arriving at the train station at dawn. Readers spend an entire book alongside the protagonists, and it should be someone fascinating enough to keep you turning pages through every moment, big or small.

9. Find a common ground between you and your characters — “steep yourself in their atmosphere.” Learn to empathize.

Sometimes the things we find most fascinating in choosing characters to write about is that they puzzle us. They’re captivating because there’s something so unlike you in that character, something you want to understand. Still, finding a common ground between you and your characters, no matter how unlike you they are, is necessary. Call it method-writing or what have you. Woolf explains it beautifully:

… to have got at what I meant I should have had to go back and back and back; to experiment with one thing and another; to try this sentence and that, referring each word to my vision, matching it as exactly as possible, and knowing that somehow I had to find a common ground between us, a convention which would not seem to you too odd, unreal, and far-fetched to believe in.

10. Describe your characters “beautifully if possible, and truthfully at any rate.”

How do you explain to people how to write about someone beautifully or truthfully? It’s something that seems near impossible — until you hear Woolf do it:

You should insist that [Mrs. Brown] is an old lady of unlimited capacity and infinite variety; capable of appearing in any place; wearing any dress; saying anything and doing heaven knows what. But the things she says and the things she does and her eyes and her nose and her speech and her silence have an overwhelming fascination, for she is, of course, the spirit we live by, life itself.

In part, what makes Woolf’s characters so timeless is that they are all relatable. Even the characters that are hard to empathize with — for example, the selfish, short-tempered Mr. Ramsey from To The Lighthouse — is relatable in a very basic, human way: He fears failure, desires a fulfilled life and is anxious to leave his mark on the world before he leaves it. These are timeless feelings — feelings that Woolf may have used as a common ground between her and even one of her most unlikable characters, and they are what keep generations going back to her work.

“Most novelists have the same experience,” Woolf explains in Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown. “Some Brown, Smith, or Jones comes before them and says in the most seductive and charming way in the world: ‘Come and catch me if you can.”

Freddie Moore is a Brooklyn-based writer. Her full name is Winifred, and her writing has appeared in The Paris Review Daily and The Huffington Post. As a former cheesemonger, she’s a big-time foodie who knows her cheese. Follow her on Twitter: @moorefreddie

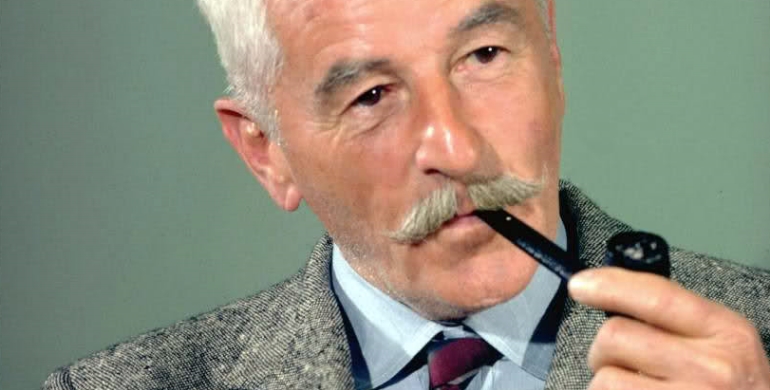

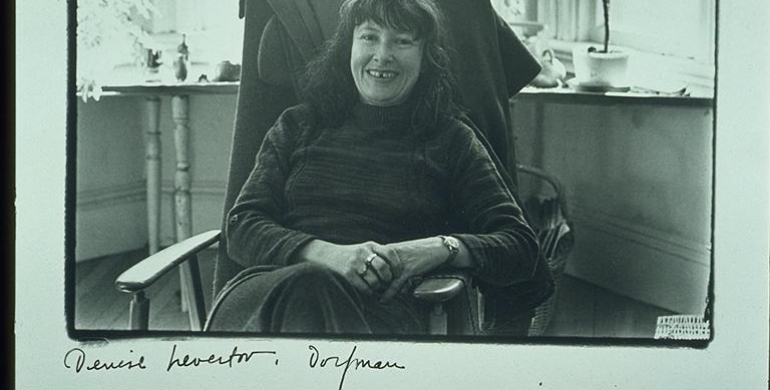

(Image credit, from top: Houghton Library)

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©