When you're a child and someone asks you what you want to be when you grow up, very few are likely to respond, "I want to give the best years of my life to a nondescript job that requires sitting in a cubicle for eight hours." And yet, that is what many of us — especially as writers — are destined for. It's not that I didn't try to avoid it through my years of higher education and ambitions; it's that I needed money and I needed it by any means necessary (barring sex work). So now here I am, five dead-end jobs into my 20s with nothing to show for it but a scant 401(k) and the merciful avoidance of needing Obamacare.

The Backstory

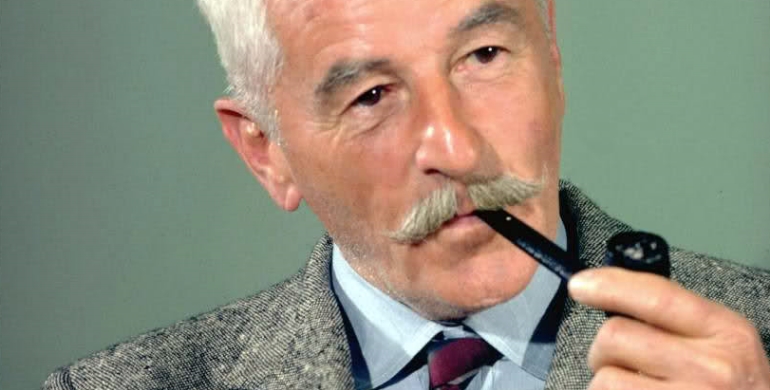

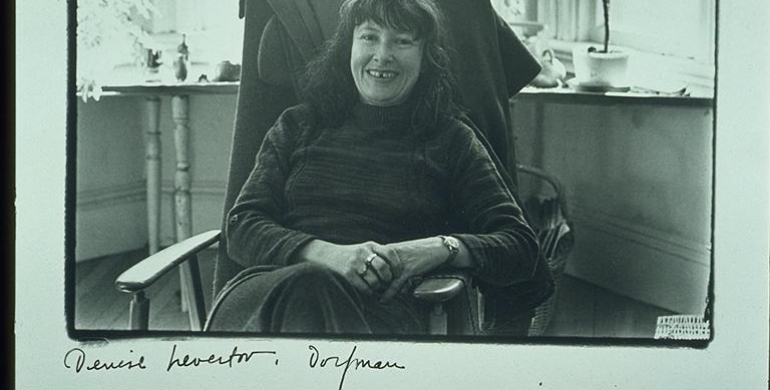

I graduated from college with a degree in screenwriting. If that isn’t some incredible indication of my naïveté, I don’t know what is. While in college, I was determined to graduate as early as possible, assuming that, once I got out, money and opportunity would come a-knockin’. I was rudely awakened to find that the only things waiting were student loan payments and a job proofreading last wills and testaments. It was all very grim — and not in a semi-dignified F. Scott Fitzgerald or William Faulkner selling their scripts and souls to Hollywood sort of way. There was no nobility to my struggle in the way I had envisioned the tireless scraping-by of past writers like Margaret Atwood, who worked in a coffee shop, Haruki Murakami, who worked in a record store, or even Patti Smith, who worked at Strand. Unlike the aforementioned, my plight was oftentimes too soul-sucking to evoke inspiration of any kind.

“Menial” Jobs vs. Office Jobs

And this brings me to the fundamental difference between “menial” jobs and office jobs: The former at least has a certain romance to it that an office job never can. The wages are lower, sure, but the hunger and desire to succeed is higher. Once you’ve surrendered yourself to office life, you become a domesticated animal, too comfortable and complacent to bother with outside pursuits. Sure, you try for awhile to continue with your real passion, but, ultimately, you succumb to going home and watching movies or TV shows every night because your mind has been drained from essentially doing nothing of value all day.

As I sat in my cube at my first job, reading about the Selena memorabilia and crystal ball someone wanted to leave their granddaughter, I wondered if I shouldn’t start making out my own will as well because that’s how dangerously I was teetering on the edge. I wondered what the point was of remaining in Los Angeles if I was never even going to find the time to make the so-called connections I would need to miraculously land a film-related job. One day, I finally decided to quit without a backup plan, leaving behind my affordable one-bedroom apartment in Los Feliz, as well as the California emblems of golden sunshine and glorious Mexican food. And what does any person without a realistic plan or goal do? Move to New York.

New Yooooork, New Yooooork

Upon moving to the city of which Thomas Wolfe once said, “One belongs to New York instantly. One belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years,” I was terrified. I had never done anything so misguided, so unthought out. I did not experience this instant sense of belonging that Wolfe was referring to. All I felt was worry and the lingering belief that I would somehow fail even worse than I had in L.A.

I quickly settled into the common New York rhythm of moving around often and unexpectedly, from Williamsburg to Harlem to Crown Heights to several hovels in Bushwick. It was exhilarating. I was finally shocked out of the coma of two years of slaving away in a cubicle and letting my mind atrophy to the point of near total disuse. And I wasn’t about to return to the cube anytime soon. This is the point where I, instead, choose to go on a two-year bender, enjoying life to its work-free fullest with my credit card — my simultaneous salvation and bane. Sure, I would work a few random freelance jobs here and there, including nebulous titles like “community manager,” but I managed to cling to as much free time as I could. Drinking and writing, always my two great loves, were things I could finally focus on again.

My second office job was as an editor for a magazine. If you’ve ever lived in New York, you know that just about anybody with a trust fund can start a magazine. I didn’t mind it, but it also didn’t pay. I count it as part of my office life because I was expected to sit in a room for a certain amount of time and pretend to work. However, maybe there is something to this not-getting-paid aspect because this was definitely the job I enjoyed doing the most in spite of still having to use my credit card to pay rent and buy food. I also got another small stipend from a writing internship for a pop culture-oriented website, though I eventually stopped going when they insisted that I interview people on the streets of SoHo about their sex lives.

The Cubicle Strikes Back

As Geoffrey Chaucer once annoyingly observed, all good things must come to an end. My semi-employed paradise was interrupted by higher monthly credit card minimums. I had to get a “real” job. And by real, I mean utterly brain-dead work that you could finish in three hours, but for some reason, you still have to stay in your shackles for eight. This time, I landed a position in the writing field, though it quickly made me never want to write again. Inexplicably, the jobs that pay the most for writing are always the most painstaking and tend to center around mundane topics that maybe one to five people give a shit about. I imagined myself as one of the office drones in David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King. I applied the feminist Betty Friedan quote about suburban housewives living in “comfortable concentration camps” to myself as an office worker. I wasn’t even really a writer. A writer could write anywhere and about whatever they wanted, but I had to be someone else’s shill. It wasn’t the same.

I tried interviewing at a number of hotels in order to break out of the cube life, but no one was convinced of my social skills. Even I wasn’t. After numerous rejections in the job fields I viewed as glamorous — barista, retail cashier, front desk receptionist — I gained some level of acceptance about the current path of my fate. And I’m not going to tell you that acceptance is key, but it will make you feel slightly less trapped if you’re suffering through an office setting.

Writing in a Cubicle

The other hurdle you must jump over is forcing yourself to keep writing outside of work, even when you feel like you just don’t have the mental capacity. It takes every modicum of strength possible to be able to write outside of a writing job — and when that’s your only skill, there’s little you can do about it. I did my best to do personal writing at work, but, frequently, the amount of writing I would have to do about inane topics would get in the way. I felt as though I was drowning in my own misery and, ironically, writing was my only method of coping through it.

Obviously, the worst part about a conventional office environment (excluding ad agencies and startups, I would assume) for someone who is creative is that you have to stifle almost every trace of yourself in order to fit in. Every day that I go to sit in my cubicle, I wonder when they’ll finally dose me with the Kool-Aid. Most of the people at my work are contented. They live in Queens or gentrified Brooklyn and see their job as something they actually want to do. It’s something that they take pride in. I know I can never be like them, and the difference becomes more glaring each day.

I can’t lie to you and tell you that there’s an easy way out. I only know that I have to keep going through the agony because I have to stay in New York and I have to keep writing. In a city where jobs that pay a living salary are hard to come by as a writer, I’m aware that I’m fortunate — though this doesn’t prevent the dissatisfaction from creeping in on a daily basis. Usually, I find that it helps if I picture David Sedaris working as an elf or Kurt Vonnegut as the manager of a Saab car dealership. I know that every great writer before me has hated any job that wasn’t writing what he or she wanted to write. But they persisted and endured, and that’s exactly what you and I have to do, too.

Genna Rivieccio graduated with a degree in screenwriting and closely identifies with Joe Gillis in Sunset Boulevard. She has written for pop culture blogs, including Culled Culture, The Toast and Behind the Hype, as well as satire for Missing a Dick and The Burning Bush.

(Image credit: Van Redin)

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©