Daniel Genis is a free man after having spent the better part of a decade behind bars for “politely” robbing folks at knifepoint to support his heroin habit. Now he is armed with a 310-page novel called Narcotica, a sober mind and body, deep insights into prison life and the knowledge that buying souls in the big house is frowned upon.

Narcotica follows the life of someone who can be described as a modern customs agent, though in an alternate post-Civil War United States where all drugs are legal. It was written partly by hand in solitary confinement and on a specially designed typewriter. The novel’s main character, like Genis, resides in New York City, part of an opiate-addicted North. (Below the Mason-Dixon line, cocaine is king.) I spoke with Genis over email about Narcotica, life in prison and what it’s like to be the smartest guy in the room.

Justin Glawe: When you realized you wanted to write, did you immediately set out to get a typewriter or did you simply begin writing by hand?

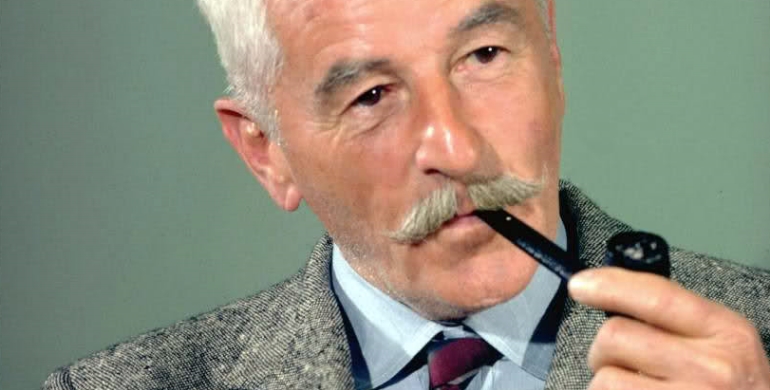

Daniel Genis: From the very first day of my incarceration, I knew that reading and writing would be my salvation in that alien environment. In the Soviet Union, they used to call this “internal immigration,” departing for a better place in one’s own head. As a result, I ordered a typewriter immediately. However, that was in 2004 and I could purchase one for only $125. Soon after, the rules changed regarding electronic equipment: Everything had to be transparent. As a result, my first typewriter was confiscated and I had to buy a new one. Only one company in the world makes such a thing, Swintec (though I’m loath to give them a plug), and they charge $375 dollars for the kind with memory — [7,000 characters] of memory, that is, because more is not allowed.

A typewriter contains enough metal rods and plastic shards to murder a fair amount of people, so one would think that this would be an issue. However, prisoners are basically poor. As a result, typewriters are not too common and someone investing in one is not suspected of taking it apart to make shanks — much easier to simply use a can top.

It’s the ribbon that was more liable to being checked, and that is because of gambling. Inside the joint, there is a huge gambling culture, and organizations of prisoners get together to run “tickets” for sports gambling. The results come from Vegas, where someone usually has a cousin who will accept collect calls. The gambling tickets themselves need to be produced en masse, so when the cops bust an operation, they try to find the typewriter that the tickets were made on to confiscate it. The way to do this is to pull the ribbon out and read it backwards. The ribbons that are easily available can be read without any trouble, only from right to left. Because of the political nature of some of my writing, I tried to avoid this issue and found a place to order fabric ribbons. Maybe the FBI can decipher them, but the DOC can’t.

A word on antiquated technology: Prison is a haven for it, and I have seen some jerry-rigged devices appropriate for a steampunk convention. When I first arrived, there were still old-timers with eight-track players, but everyone else relied on tape players. There is a specialized company, based in Thailand that will put any CD on a tape (which can’t have screws) and ship it to prison for $20. Selling the actual clear equipment is another racket. Because of the “captive market,” the companies can charge whatever they want, so one sees $80 Walkmen and the aforementioned $375 typewriter. Same with beard trimmers and table fans.

Writing by hand was often a requirement, especially because I wrote my novel in solitary confinement. The whole 310-page mass of it was written on the backs of official papers and unfolded envelopes and cardboard chunks because I was only allowed five pieces of paper a week. So I came out of solitary with this mass of scribbled bits and pieces that I then typed out on the typewriter that had been rotting in storage while I served my box time.

What was your writing process like?

My novel had been burbling inside of me for a while. Before going to prison, I had two years of addiction, which did not help the creative process one bit. It was only once I got the chemicals out of my system that I could process the experience and (hopefully) make literature out of it. In a sense, my short use of drugs cost me an enormous amount of life. I felt that drugs owed me and wrote a novel “exploiting” them as far as I could. First I had to read all the literature of drugs. It goes back as far as Herodotus mentioning the Scythians throwing hemp seeds on hot rocks in a tent and screaming with joy from the results, but I have also made a thorough study of DeQuincey and Crowley and Burroughs and Trocchi and Huxley and Philip Dick and [Jim] Carroll and Richard Hell and anyone else who wrote on the subject, including lots of academic work on the chemistry of narcotics.

After all of that reading, the tale just poured out of me while I was in solitary confinement. It’s 310 pages, an alternate history with a philosophical bent about what the world would be like if drugs were the drug of choice of society (rather than alcohol). Lots of history play and arcane references, but the novel can also be read just as an adventure story. There are levels to it. The editing process, once I had access to my typewriter again, took longer than the original composition. Like Athena, Narcotica burst from my head fully formed!

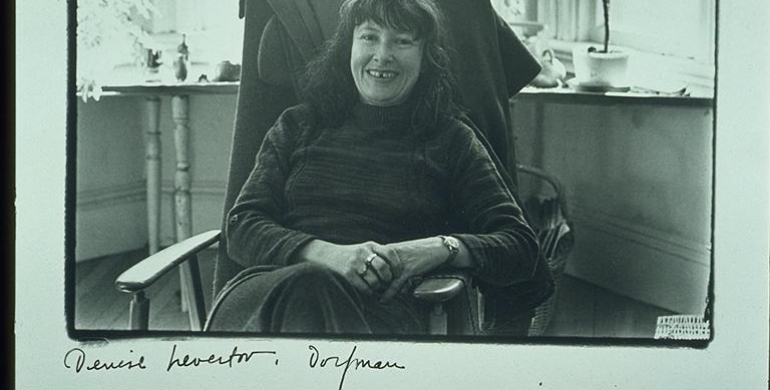

Genis and his wife during a prison visit

I would think having that much free time and, in your case, solitude would be great for the writing process. Would you recommend a lengthy prison sentence with bouts of solitary confinement to other aspiring writers?

First of all, let me say that I am grateful for prison for allowing me an extra 10 years to pursue my interests and read, read, read. I have a particular interest in Sir Richard Burton and had the time to read most of his long-winded 19th century travelogues. Just recently Murakami had an assassin character say in 1Q84 that a prison cell is the only proper place to read Proust in our hectic modern world, and I laughed out loud because I already knew this from first-hand experience. Same for Joyce and Musil, and Gormenghast and Dr. Johnson .... I was able to read all the big, important and long works at my leisure.

As good as solitude is for writing — and the police don’t care what you are doing as long as you are not shaming them in print or cutting up your neighbor — prison is hardly a serene place. In solitary, there was howling, crying, head banging, daily medical emergencies, food fights, shit fights and any other assault men can think of under such limitations. To be honest, while writing Narcotica I had a bunkie in the cell with me. I had hurt my back recently and was issued muscle relaxants that had a soporific effect, so I just fed him a pill after every meal and kept him asleep so I could write in peace.

What did the other prisoners think of you in general and your writing in particular? Did you share any of your work with them?

When I came to prison, it was very obvious that I was massively out of place. I quickly had to make a decision: Would I try and fit in by expressing an interest in pit bulls and Harley Davidson motorcycles? Or would I be myself and make them respect me anyway? I took the more challenging path, and it worked just fine for me.

On top of that, Narcotica made me somewhat of a jailhouse celebrity. Perhaps 300 prisoners read it, in typewritten form, as I would give it to anyone with the education to handle the book. They respected the achievement very much and even loved me for it. Every few days, I receive nice letters from guys still in that hell. I also worked in prison libraries and guided the convicts’ reading away from James Patterson to authors like Cormac McCarthy and Nabokov (Lolita was popular). As a result, I brightened many lives and would like to think that, through the power of culture, improved them.

I was in 12 prisons, and towards the end, they all knew who I was before I got there and there would be a line of people waiting to read Narcotica. I once tested it on myself and finished the novel in six hours, so I gave them each a week with it. Sometimes guys would underestimate what it was and couldn’t really handle it because they thought it would be some gangster tale about drugs. But anyone who read Brave New World or 1984 or Chesterton or Hesse (and there are plenty of serious readers in there) got a huge kick out of. I only hope that I can replicate this success here in the real world.

Justin Glawe has been to jail, but never prison. He chronicles crime and violence in his hometown.

(Image credits, from top: Petra Szabo, Swintec, Daniel Genis)

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©