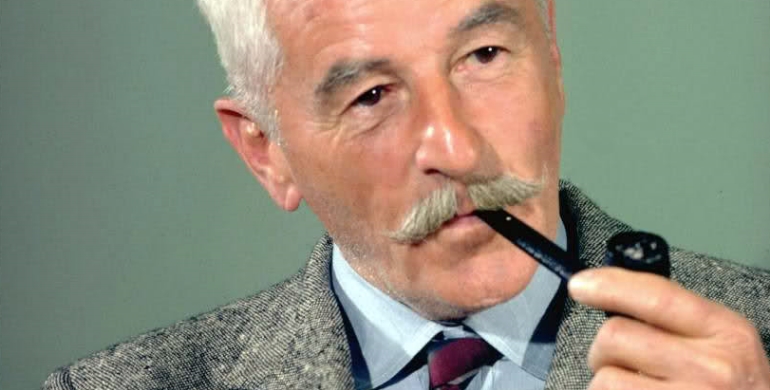

Ernest Hemingway (via Flickr)

A diamond solitaire, blue jeans, missionary-style sex — what do all of these have in common? They are classics, simple, no-frills staples that get the job done. But in a world gone mad with extravagance (think the Kardashians), the basics have lost much of their luster, and along with them, the simple sentence suffers. In its place are verbose strings that meander as if through a hedge maze, leaving you tired and wondering how you got there and what the hell was the point.

Some writers of the verbose sentence are talented, without question. Their mastery of language is evident. But as I read, I can almost feel them behind me, jumping up and down and pointing at the page, practically knocking the book out of my hand, saying, “Look what I can do!” In these sentences, the writer is ever present, the reader is lost.

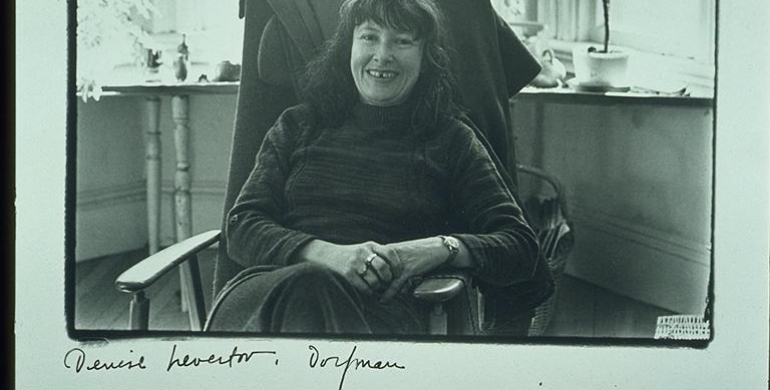

Atonement by Ian McEwan (via Happy Antipodean)

Consider this sentence from Ian McEwan’s Atonement:

“The labor in the kitchen had been long and hard all day in the heat, and the residue was everywhere; the flagstone floor was slick with the split grease of roasted meat and trodden-in peel; sodden tea towels, tributes to heroic forgotten labors, drooped over the range like decaying regimental banners in church; nudging Cecilia’s shin, an overflowing basket of vegetable trimmings which Betty would take home to feed to her Gloucester Old Spot, fattening for December.”

All one sentence. The language is rich, undoubtedly, but there are — or could be, by my count — three, if not four, sentences in that one. By the end, we’ve been given so much information that I have to go back and re-read it to remember where we started. Not that I’m one to shy away from work, but why do that to the reader?

In Our Time by Ernest Hemingway (via Simon & Schuster)

Now consider this, from Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time:

“The first German I saw climbed up over the garden wall. We waited till he got one leg over and potted him. He had so much equipment on and looked awfully surprised and fell down into the garden. Then three more came over further down the wall. We shot them. They all came just like that.”

Six sentences. To be fair, in the world of simple sentences, Hemingway is King. But the above is an example of a writer who trusts the reader to fill in the gaps. I don’t need a wordy sentence to see the faces of men meeting their end, to hear the thuds of their felled bodies. I don’t need a wordy sentence to know war is hell. Good, simple writing will do that.

But there is more to all this: I can’t get past the creeping suspicion that elaborate sentences are like a magician’s trick, smoke and mirrors, or a politician’s rhetoric, an abundance of words without anything to say. They can be impressive, yes, but are they honest? Simple sentences carry with them truth — and if they don’t, it’s easy to spot. Complex sentences bury their meaning under layers of embellishment. So let’s stop trying to impress each other and just be real. Keep your bombastic, grandiloquent sentences if you must, but build them upon a solid foundation of clean, simple, honest ones.

Trisha Leon is a freelance writer and student of English at Cedar Crest College in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©