(via Flickr)

A writer’s biggest frustration is language itself. You’ll be scribbling through an afternoon, words tumbling onto the page one after another, your brain and pen for once not squabbling but in perfect sync — and then you’ll swerve into a ditch. A chasm will have opened up, one that stinks foul and no amount of flipping through a thesaurus will help you cross. You’ve hit an emotion and you can find no way to describe it, no word or phrase to bridge the gap.

Some languages navigate these pitfalls better than others. German, obligingly following stereotype, is precise and efficient, taking compounds to a new level, never reticent to throw two, three or four words together if the situation calls for it. “Vergangenheitsbewaltigung” means struggling to come to terms with the past. “Sitzpinkler” is a man who sits down to pee. “Eisenbahnscheinbewegung,” which never fails to bring a smile to my face, describes the sensation of sitting on a train you think is moving, only to find out it is actually the adjacent train that is in motion.

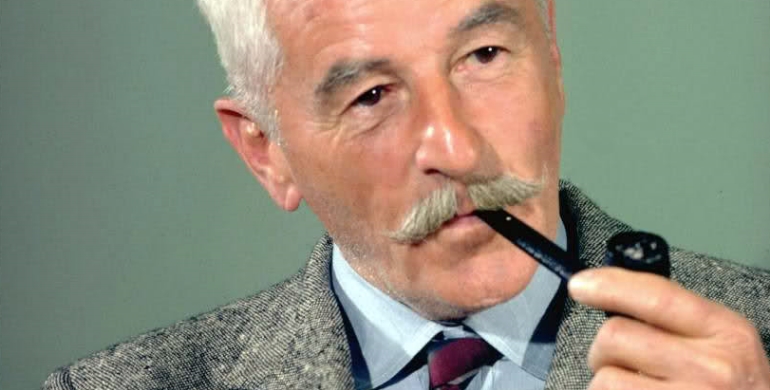

George Orwell’s passport photo (via Wikipedia)

All in one word! The opposite of George Orwell’s Newspeak, expanding vocabulary by creating more nuanced, specific and fine-grained words, broadening the possibilities of human expression. Orwell proposed just this: a real-life ministry for language charged with inventing new words for phenomena we haven’t yet labelled. We come up with words for new technology all the time, but rarely do we try to name new emotions, novel feelings that bubble up in that swirling, gurgling morass inside us.

Yet we should. So many of us go through incredible bouts of loneliness because we search for understanding and fall short. Language is all we have to represent these shapeless forms we call feelings, those that terrorize our minds, ebbing and flowing like waves at the behest of a moon or a God or some wicked torturer. All we can do is use language to vent. Surely the more words, the better.

However, coining new words won’t change the fact that these spirits, these significant chunks of human existence, remain trapped inside our skulls, inaccessible fully to anyone but ourselves. Words will always fail us because their real world anchors are so slight, only a fragment of description, able to capture neither the essence nor the sum of the thing.

Take the word “tree.” It works because trees exist in the physical world. You can experience a tree for yourself, see it, smell it, rub up against it. From then on the word has a solid, shared meaning.

But when it comes to “depression,” “regret,” “remorse,” “ecstasy” or “love,” there is no objective experience to share. We can’t stand in a garden and gaze at regret, point over the road to ecstasy or smell the rancid stench of depression. Nor can we define emotions with other words, because those other words are always emotions too. We get trapped in a big swinging, torturous cycle, chasing our tails like dogs that can’t bark.

Of course emotions do have real world manifestations : tears, a smile or gritted teeth. We can measure brain activity, see which synapse fires when, the balance of chemicals in certain moods and so on. But these descriptions are always vague apparitions, the ghosts of understanding. We’d never consider happiness explained by a smile and a few overactive dopamine receptors, nor anger by a punch to the face.

Orwell believed video was the only way to expose this inner life:

If one thinks of it there is very little in the mind that could not somehow be represented by the strange distorting powers of the film. A millionaire with a private cinematograph, all the necessary props and a troupe of intelligent actors could, if he wished, make practically all of his inner life known.

But is this true? Imagine you were the millionaire. First you’d have to explain to the actors the scene they were supposed to act. Words, again, would fail you. And even if they didn’t, after thousands of rehearsals and tiny adjustments in every inflection, stance and action, you’d still never get it because everything in our heads is formless. We don’t see a film reel flickering, we feel life.

You could rely on surrealism and symbols, flashes of light and color in one corner, loud crashes and soft whistles in another , hitting all the senses in an effort to imply how you feel. And if by some stroke of luck you managed to recreate the feeling exactly — the outside world an echo chamber for your inner, with perfect harmony between the two — you’d still be at the mercy of interpretation. A green flash will mean “go” to some and mould to others. Red will be sex or blood. A loud noise might be excitement or fear. A crashing sound may conjure a fond memory of somebody’s mother rattling through the pan drawer or the memory of a sister being buried alive.

And people wonder why writers become tense, angry drunks, tapping through the night, slugging whisky, tearing paper and screeching inside and out. Because language doesn’t cut it. Whatever you write will always be a poor imitation of what you really mean. You’ll always feel like a fake. And hopefully this will force you to keep mashing at your keyboard until the flesh falls away from your fingers in a fruitless quest for honesty, creating something spectacular along the way.

Joseph Todd is a London-based writer of politics, culture and philosophy. He is currently working on his first book, scribbling his way through more articles and trying to find excuses to fling himself to faraway parts of the world.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK AND PINTEREST.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©