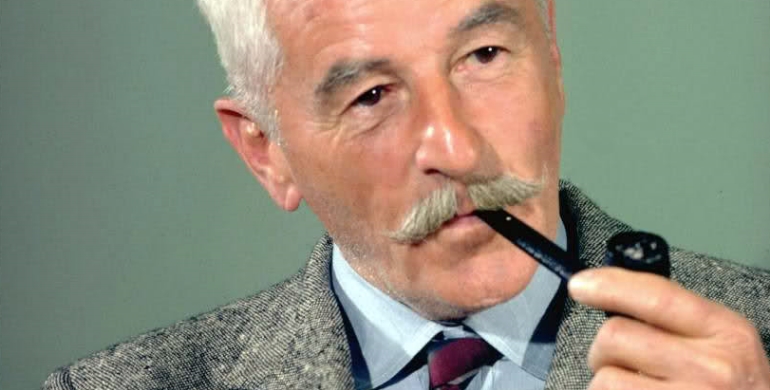

Jean-Paul Sartre in Venice, 1967 (via Wikipedia)

On October 22, 1964, Jean-Paul Sartre refused the Nobel Prize in Literature, setting a precedent and an example for other writers.

Exactly 50 years ago today, Jean-Paul Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “his work which, rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age” — but he refused it. It's especially difficult for a writer to understand such an action. Sure, we write because we're compelled to, because it's our passion, but how could someone turn down such an accolade — and all that money? Most writers struggle financially, even if they publish regularly. And even though we don't admit it, we all aspire to achieve that level of recognition. But in his letter to the Swedish press on October 22, 1964, Sartre wrote that a writer must “refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honorable circumstances.” For Sartre it was all about authenticity — but authenticity as an existentialist defines it.

If you know anything about Sartre’s philosophical writing, then you know that it requires taking full responsibility for your life, your choices and actions. Since there’s no Creator, according to Sartre, then human beings come into existence without any predefined nature or essence and it’s up to us to continually define ourselves. In a 1946 lecture titled “Existentialism is a Humanism,” Sartre states the fundamental principle of his philosophy: “Man is nothing else but what he purposes, he exists only in so far as he realises himself, he is therefore nothing else but the sum of his actions, nothing else but what his life is.”

Sartre and his partner Simone de Beauvior’s grave in Paris (via Flickr)

So if you’re a writer, then you’ve made yourself into a writer — you’ve made writing your purpose in life. And while you may tell yourself that you’re not really concerned with winning awards and prizes for your writing, you have to admit that you look at the Nobel Prize with some longing. I mean, if you’ve put a lot of time and energy into being a writer, you’re not grinding away at your craft so no one else will read it, right? You want some kind of audience. You want to share your ideas and opinions and, yes, your talent with the world. And Sartre’s existentialism tells us that sharing ourselves with the world may even be a necessity. In that same lecture, he states that a person “recognises that he cannot be anything (in the sense in which one says one is spiritual, or that one is wicked or jealous) unless others recognise him as such. I cannot obtain any truth whatsoever about myself, except through the mediation of another.”

And unless you’re a robot, you probably feel some disappointment from the fact that you’re not yet a renowned writer, not a Stephen King or a Suzanne Collins — or even a Jean-Paul Sartre. You may be envious-yet-hopeful, or you may have succumbed to a resentful pessimism. But Sartre’s existentialism shows us that this attitude is not only unhealthy, but unnecessary. In the same 1946 lecture, Sartre addresses this outlook, saying:

Many have but one resource to sustain them in their misery, and that is to think, “Circumstances have been against me, I was worthy to be something much better than I have been. ... If I have not written any very good books, it is because I had not the leisure to do so.”

Some of us may feel this way, at least occasionally. Maybe we are struggling to further our education while trying to put food on the table for our family and have no time or energy left over to complete that novel, or maybe we feel that we’ve had the time and energy to work on our craft but simply haven’t had the good fortune to be “discovered” yet. There are a thousand reasons why we could surrender ourselves up to pessimism and resignation. But Sartre’s philosophy asks us to look again at the situation:

There is no genius other than that which is expressed in works of art. The genius of Proust is the totality of the works of Proust; the genius of Racine is the series of his tragedies, outside of which there is nothing. Why should we attribute to Racine the capacity to write yet another tragedy when that is precisely what he did not write? In life, a man commits himself, draws his own portrait and there is nothing but that portrait.

While this may sound pessimistic on the face of it, Sartre reminds us that “it puts everyone in a position to understand that reality alone is reliable; that dreams, expectations and hopes serve to define a man only as deceptive dreams, abortive hopes, expectations unfulfilled; that is to say, they define him negatively, not positively.” But an existentialist view refuses to define humanity negatively. Sartre sums it up nicely when he says:

You have seen that [existentialism] cannot be regarded as a philosophy of quietism since it defines man by his action; nor as a pessimistic description of man, for no doctrine is more optimistic, the destiny of man is placed within himself. Nor is it an attempt to discourage man from action since it tells him that there is no hope except in his action.

So if you’ve chosen to be a writer, great! Put that nose to the grindstone and churn out your best work. Sartre just asks that you self-consciously commit to it and that you remind yourself frequently that you’ve chosen this destiny, that your path in life is the result of your choices and actions — otherwise you’re not living authentically. And who knows, maybe someday you’ll even get to refuse the Nobel Prize just like Sartre did.

Steve Neumann is a writer, teacher and philosophile. He used to blog at Rationally Speaking, and you can read his sporadic random tweets at @JunoWalker.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©